Articles

China-Russia summit diplomacy was in overdrive this June when Chairman Xi Jinping and President Vladimir Putin met on four separate occasions. In early June, they declared that the Russian-Chinese strategic partnership relationship entered a “new age,” while celebrating the 70th anniversary of diplomatic relations. Barely a week later, Putin and Xi attended the 19th SCO Summit in Bishkek. From there, they joined fifth Interaction and Confidence-Building Measures in Asia (CICA) Summit in Dushanbe. At the end of June, they were part of the G20 Summit in Osaka, where they joined in a mini Russia-India-China (RIC) gathering with Indian PM Narendra Modi before meeting separately with US President Donald Trump. There was also a significant upgrade in joint activity by the militaries. It began with the maritime stage of the annual Joint Sea naval drill in the Yellow Sea in early May and ended with China’s participation in Russia’s Center-2019 exercises on Sept. 16-21. In between, Russian and Chinese bombers conducted the first-ever joint patrol over the Sea of Japan and the East China Sea. Meanwhile, Chinese analysts actively deliberated the nature, scale, depth and limits of China’s “best-ever” relationship with Russia. The consensus seemed to move ahead with closer ties across board.

Two statements for the “new era”

Chairman Xi Jinping’s three-day trip to Russia on June 5-7 was his eighth official visit to Russia and his first in his second term as chairman of the Chinese Communist Party. In Moscow, Xi and President Vladimir Putin upgraded existing bilateral ties to a “comprehensive strategic partnership of coordination for a new era.” The two leaders had met 28 times prior to this point. This time, the “new era” coincided with the 70th anniversary of Chinese-Russian diplomatic ties.

In the Kremlin, Putin and Xi discussed major bilateral issues and reviewed progress in implementing major economic and humanitarian projects “in a business-like and constructive manner,” said Putin after the talks. Xi described the talks as “very productive,” particularly in trade and economics. The “new era” of Beijing and Moscow’s “comprehensive strategic partnership of coordination” was marked by two statements: The Joint Statement on Developing Comprehensive Partnership and Strategic Interaction Entering a New Era and Joint Statement on Strengthening Global Strategic Stability in the Modern Age.

Much of the “new era” statement meant “high politics,” meaning political/diplomatic (5 items), security (7 items) and global affairs (23 items). “Low politics” covered economics (17 items) and humanities (11 items). The statement on strategic stability is devoted exclusively to areas of arms control: nuclear, missiles, outer space, chemical and biological weapons.

The focus on high politics reflected a growing concern about the fluidity, instability and uncertainty in a world in which the forces of radical change both within the West, and between the West and the rest are growing. These changes are accelerating because of the rise of populism and their charismatic leaders. The radical de-linking of the US from various bilateral and multilateral mechanisms was seen as further straining the global liberal international order (LIO). Trump’s trade war with China and other US economic partners could lead to further weakening, if not destruction, of the global trade system. For China, and to a lesser degree for Russia, the current LIO which is dominated by the West, needs to be preserved through incremental reforms – not dumping the “baby” (LIO) out with the bath water.

The strategic stability statement signed in Moscow addressed a growing concern of the two countries. For the first time, the global arms control and nonproliferation infrastructure is on the brink of collapsing. Currently, the only remaining arms control treaty is New START, signed during the Obama administration, and is due to expire in 2021. On Aug. 19, the U.S. tested a medium-range cruise missile following its exit from the INF treaty two weeks prior (Aug. 2). The US was also looking for countries in the Asia-Pacific to host the deployment of these missiles. For both Russia and China, US unilateral pursuit of both offensive and defensive superiority means the end of MAD, or mutually assured destruction, which has been the bedrock of the global nuclear balance and stability since the Cold War. The end of MAD, according to Ji Zhi-ye (季志业), a Russia specialist in a top think tank in Beijing, means that the US, with both offensive and defensive capabilities, is more likely to consider a nuclear option. As a result, the wording of the current strategic stability statement regarding US behavior is more direct and sharper than that of the 2016 strategic stability document.

In the context of these radical changes, the “new era” of Chinese-Russian strategic partnership was seen not only as serving the interests of the two powers themselves, but is also an important force for maintaining world stability. The “new era” of strategic partnership for Moscow and Beijing, both being “strategic competitors” of the US, would ensure the two coordinate their respective policies toward Washington.

The momentum of summitry continued in the next few weeks when Xi and Putin met three more times at multilateral events: the 19th Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) Summit in Bishkek on June 14, the fifth Conference on Interaction and Confidence-Building Measures in Asia (CICA) in Dushanbe on June 15, and the Russia-India-China (RIC) meeting on the sidelines of the G20 summit in Osaka on June 28.

Still the economy, not so stupid

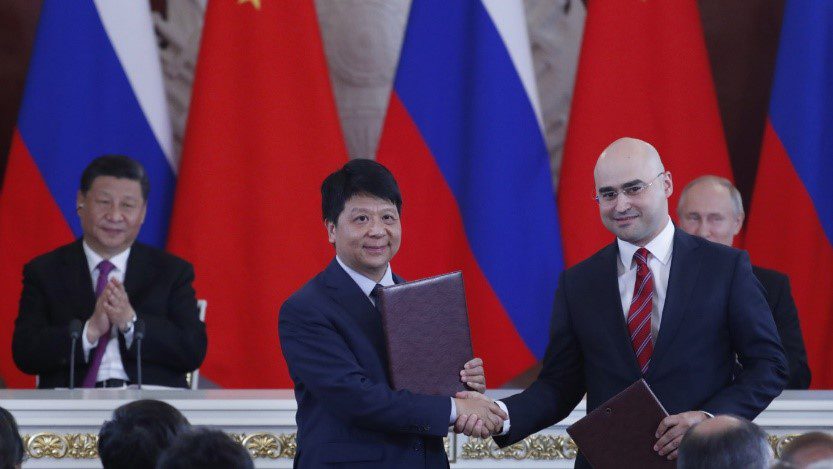

Xi’s three-day Russia visit featured several high-profile business-related items, including attending the second Russia-China Energy Business Forum and the 23rd St. Petersburg International Economic Forum. Following the Kremlin talks, Xi and Putin presided over the signing of 23 agreements mostly in the economic area, covering trade, investment, 5G, soybeans, e-commerce, joint science and technology development, aviation, automobile, energy, nuclear power, and cultural cooperation. Xi’s visit also coincided with the opening of an assembly plant by China’s Great Wall Motors in Tula of Russia (165 km south of Moscow) with an initial annual capacity of 80,000 vehicles. Putin and Xi even took time during their talks in the Kremlin to inspect several models of Great Wall Motors on display in the Kremlin compound. The $500-million plant is China’s largest investment in Russia’s manufacturing sector.

In Moscow, the two leaders also decided to start a two-year project on “Russian-Chinese scientific, technical and innovation cooperation.” The two sides have been working on projects in space exploration, nuclear energy, fast-neutron reactor, biotechnology, and pharmaceuticals. At the annual Moscow Airshow at the end of August, a range of joint projects were on display, including a real-sized portion of the cockpit and passenger cabin of the CR-929 long-range wide-body civilian aircraft. The 250-to-320-seat twinjet airliner, equivalent to the Airbus A-330, was launched in 2011 and is scheduled for its first test flight in 2025.

“There is no end to the development of China-Russia relations,” Xi said following the signing of agreements. About 30 investment projects worth a total of $22 billion were underway with Chinese investors, according to Putin, including $3.5 billion invested in the Russian Far East. Other projects included the third stage of Russia’s Yamal LNG plant to be operational in November. China holds 29.9% of its share. Moreover, Russia now welcomes China’s investment in another large project – Arctic LNG2. A Russian gas pipeline to China along the so-called eastern route will go into service in December.

The Xi-Putin talks also gave attention to expanding regional and local interactions between the two countries. Two additional interregional cooperation mechanisms were set up between Russia’s Central Federal District and North China, as well as between Russia Northwestern Federal District and the maritime provinces of Southeast China. Already, the Volga-Yangtze Council had been functioning for several years with more direct interaction between localities of Russia and China.

Xi’s visit coincided with a symbolic turning point: for the first time in history, bilateral trade exceeded the $100 billion mark, a nearly 30% increase over that of 2017. Bilateral trade for 2019 is projected to increase another 30% to $137 billion. Although this figure is still over-shadowed by the $419 billion US-China trade, the momentum is clear.

Russia’s MTS Signs 5G Deal With Chinese Telecom Giant Huawei. Photo: Moscow Times

Ironically, the US-China trade war and US sanctions against Russia since the 2014 Ukraine/ Crimea crises may have promoted economic ties between Russia and China in at least three areas. One was high tech, particularly 5G and related IT industries. Two days after the Trump administration declared a national emergency on May 15 regarding “threats” against US technology, a move explicitly made against China’s telecom giant Huawei, Russian telecom giant VimpelCom (ВымпелКом), the third-largest wireless and second-largest telecom operator in Russia, announced that Huawei equipment did not have security issues and it was ready to launch in Moscow and St. Petersburg, which was using Huawei for 85% of its components. By the end of September, the two largest Russian cities’ entire network would go to Huawei, according to Sputnik. On June 6, Russia’s top cellphone operator MTS signed an agreement with Huawei to develop 5G technology, while Xi and Putin presided over the signing ceremony.

Unveiling the multimode multi-frequency for global signaling” chip in Kazan, Russia, August 31, 2019. Photo: Chinanews.com

Other areas of high tech were moving ahead as well, including the integration of China’s Beidou (北斗) satellite system with Russia’s GlONASS (ГЛОНАСС), cooperation in remote sensing, heavy rocket engines, and joint moon exploration. The two sides started cooperation in space-related areas some years ago. In St. Petersburg, Dmitry Rogozin, director of the Roscosmos State Corporation for Space Activities (Роскосмос), revealed that Russia was negotiating with China more joint efforts in the future. At the sixth Session of the China-Russian Committee of Strategic Cooperation for Satellite Navigation held in Kazan, Russia, the two sides indicated that they were poised to implement the cooperation accord between China’s Beidou and Russia’s GlONASS satellite guiding systems. The two sides went as far as to unveil a joint “multimode multi-frequency for global signaling” chip (全球信号多模多频射频芯片) to connect their satellite systems.

The biggest potential for Chinese-Russian economic relations is perhaps agriculture, which, for the first time, was prioritized for high-level meetings. In 2018, Sino-Russian agricultural trade topped $5.23 billion, a 28% increase over 2017. Although this was only a fifth of US agricultural export to China, there has been a steep decline of US farm products to China, a 70% drop from July 2018 to April 2019 as US soybean exports to China dropped by 87%. In normal times, a third of China’s annual soybean imports, or 32 million tons, would come from the US. The trade war with Washington, provides Russia with a unique opportunity to dramatically expand its soybean and other agribusiness exports to China. In early July, China officially gave greenlights to soybean imports from all parts of Russia, a surprisingly generous gesture toward its northern neighbor. Russia’s ability to meet China’s appetite, however, is limited: its annual soy production is only 3 million tons, or 10% of China’s need of 32 million tons. In 2018, China only imported 817,000 tons of Russian soybeans.

To accelerate Russia’s grain export to China, the COFCO, China’s largest agribusiness group, started to invest in Russia’s Far Eastern regions to develop local agricultural infrastructure and output. In 2017, COFCO set up a branch office in Vladivostok. By 2024, Russia plans to increase its exports of agricultural products to $45 billion. For that goal, Russia was willing to provide Chinese investors 118,000 hectares of land for agricultural development.

Following the formal activities in Moscow, Xi and Putin traveled to St. Petersburg for the city’s 23rd International Economic Forum (SPIEF), together with a thousand Chinese businessmen and governmental officials. Both Xi and Putin joined the second Russian-Chinese Energy Business Forum on the sidelines of the SPIEF.

Pandas, parties (at Bolshoi Theatre) and personal touches

Part of Xi’s visit to Russia was for the 70th anniversary of diplomatic relations between the two countries. In Kremlin talks, Putin started by noting that the Soviet Union recognized the PRC immediately after it was established. “Over this period, many events have happened, but in the last few years, Russian-Chinese relations have reached, without exaggeration, an unprecedented level,” continued Putin, while not mentioning the not-so-pleasant years of conflicts between the two communist giants. Ironically, it was during later times when both countries had transformed themselves substantially away from earlier and more orthodox forms of communism that they began learning how to live with one another peacefully. In other words, Russia and China became friends despite their domestic systems being so different.

Xi echoed Putin’s tribute to the Soviet role in the 70 years of diplomatic ties. “The Soviet Union was the first country to recognize our country, from the first day of establishing a new China. Over these years, Chinese-Russian relations withstood trials, changes in global affairs and changes inside our countries. Step by step, we managed to take our relations to the highest level in their entire history,” said Xi and then adding a more forward-looking statement: “I would like to say that both of us have passed the test before the peoples of our countries. The 70th anniversary is an important milestone and a new start.”

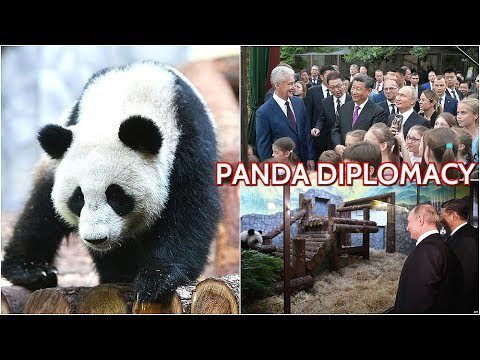

Vladimir Putin and Xi Jinping at the Moscow Zoo. Photo: Russia Insights

For this new start, Xi and Putin went to the Moscow Zoo to inaugurate the Panda Pavilion, where giant pandas (Ru Yi and Ding Ding) just started their 15-year residency, which is a symbol of good will from China and also part of an international program to preserve, protect, and research these animals. The last time Muscovites saw pandas was in 1957.

From the zoo, Putin and Xi went to the famous Bolshoi Theatre. After touring a joint photo exhibition of Chinese-Soviet/Russian relations by TASS and Xinhua, the two leaders attended a concert by the Pyatnitsky State Academic Russian Folk Choir and the China National Traditional Orchestra, which was held on the Bolshoi’s historical stage.

After all these activities on the first day of the summit, Putin and Xi continued their one-to-one talks until midnight. “We had a lot to discuss,” revealed Putin the following day. Putin then apologized to Xi that “I should let you go. Hosts should not treat their guests this way.”

The Putin-Xi intimacy continued in St. Petersburg the following day when the two visited St Petersburg State University where Xi was awarded an honorary doctorate by Rector Nikolai Kropachev. The two leaders then took a walk around the Northern capital, strolled down the city center, enjoyed a boat ride, and visited the State Hermitage Museum, while continuing their informal conversation throughout. After the sightseeing tour, Putin and Xi had another long talk in the Winter Palace focusing on global and regional issues.

In his speech to the Plenary Session of the St Petersburg International Economic Forum the following day (June 7), Putin said that Russia maintained “very deep and wide-ranging relations with China; in fact, we don’t have such relations with any other country. Indeed, we are strategic partners in the full sense of this word. We can say this without any exaggeration.”

The chemistry between the two leaders seemed to have some spillover effect for general society, as more Russians and Chinese visited each other’s country. 2018 was a record year with 2.2 million Russians traveled to China while 1.7 million Chinese went to Russia, a 21.1% increase over 2017. Meanwhile, Chinese tourism to the US fell in 2018, by 5.7% to 2.9 million, the first dip in 15 years of linear growth.

Military-to-military: from exercises to operations

Beyond what the Chinese media described as Xi’s “month of diplomacy” (外交月) and the growing personal touches at both top and lower levels, the Russian military is reportedly moving toward more military deals with China. The services of the two militaries were also preoccupied with their own joint actions. The naval part, or the second stage, of the annual Joint Sea-2019 naval exercise in the Yellow Sea started May 1 after the coastal part of the exercises were completed on April 29-30. Two submarines, 13 surface ships, as well as fixed-wing airplanes, helicopters, and marines participated in the exercise. The annual drill carried out the joint air defense, joint anti-submarine, joint submergence rescue, and other subjects. The exercises reportedly conducted involved three new joint operations: rescuing each other’s submarine crews, joint anti-submarine operation by ship-born anti-sub helicopters, and launching short-range ship-to-air missiles to neutralize incoming anti-ship missiles (May 4). All of them were the “first-ever,” or breakthroughs (突破性), for the Joint Sea series and the PLAN with any foreign counterparts. The Chinese media described the drill as conducted with “high-level mutual trust, deep interoperability and real combat-like” (高度互信, 深度融合, 紧贴实战).

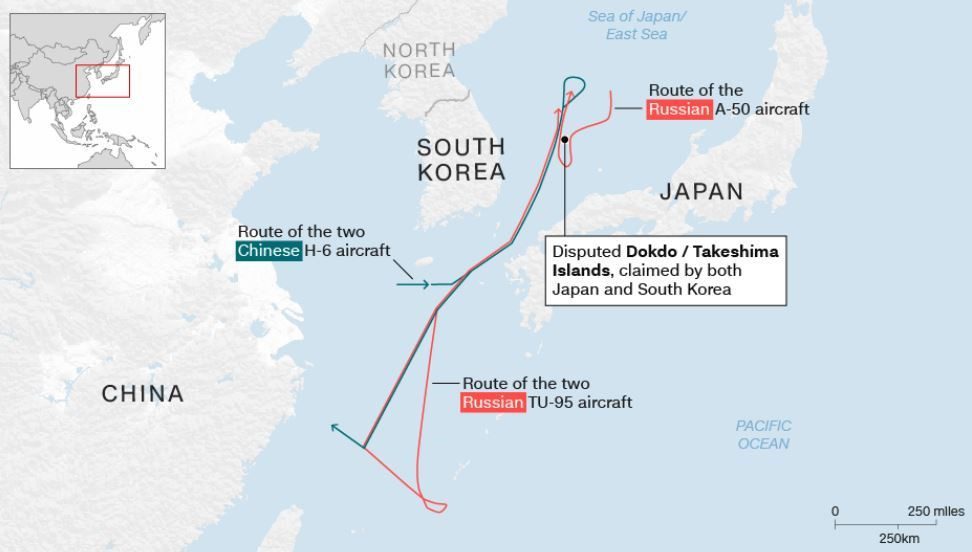

The two naval “breakthroughs” were matched on July 23 with the first long-range joint air patrol by the Chinese and Russian air forces. Two Russian Tu-95 strategic bombers and two Chinese H-6 bombers, accompanied by early warning planes (a Russian A-50 and a Chinese KJ-2000), conducted a predetermined flight route over the Sea of Japan, the East China Sea and the Tsushima Strait between South Korea and Japan (see flight map below).

Flightpath of Chinese and Russian planes over the Sea of Japan, the East China Sea, and the Tsushima Strait. Source: thesun.co.uk

Both South Korea and Japan scrambled their own jets to intercept the Russian and Chinese planes while accusing Russia and China of violating their airspaces. South Korean warplanes fired hundreds of warning shots (Moscow insists these were only flares) toward the Russian A-50 military aircraft, according to South Korean defense officials.

Russia denied that its bombers breached South Korea’s air defense identification zone (KADIZ), and insisted that this designation was not supported by international rules and that no third country’s airspace was violated. In its turn, China reminded Seoul that its KADIZ was not the same as South Korean internationally recognized airspace, and is therefore not off-limits to aircraft of other countries. The Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson also warned Seoul to “be careful when using the word ‘invasion’.”

Defense officials in Moscow and China described the joint patrol as one “carried out with the aim of deepening Russian-Chinese relations within our all-encompassing partnership, of further increasing cooperation between our armed forces, and of perfecting their capabilities to carry out joint actions, and of strengthening global strategic security.” Some in the Chinese military defined the joint patrol as a “strategic patrol” (战略巡航) and indicated that such operations would continue. The Russian side confirmed it as Dmitri Trenin, director of the Carnegie Moscow Center, believed that such patrols will become a “regular feature” under a new agreement soon to be signed between China and Russia. It is not clear if this “new agreement” is a different document from the one signed by the two militaries on an annual basis, usually on Dec. 1, for the following year’s military-to-military projects. The joint patrol, strategic or not, was a breakthrough as an operation, which is qualitatively different from the almost routinized annual exercises between the two militaries, such as the Joint Sea 2019.

But even in the more conventional mil-mil cooperation areas such as annual drills, the trend is to deepen and broaden interoperability between the two militaries. In late August, Russia and China announced that China’s military will participate in Russia’s “Center 2019” (Центр 2019) strategic command and staff exercises (командно-штабные учения) to be held Sept. 16-21, mostly at the training grounds of the Central Military District (Центрального военного округа), though some events will take place in the Arctic. 13,000 servicemen will be involved including 10,700 Russian troops and 2,250 foreign troops from China, India, Pakistan, and Uzbekistan, as well as three CSTO countries (Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan). More than 20,000 pieces of military equipment, 600 aircraft, and up to 15 ships will be involved in maneuvers.

Center exercises are held every year in a different region of Russia, which means every year one of Russia’s four large military districts (Western, Central, Eastern and Southern) hosts the large-scale exercises. This year, the bulk of the exercises will be carried out in six training grounds in Russia’s Central Military District: Totsky (Тоцкий), Donguz (Донгуз), Adanak (Аданак), Chebarkulsky (Чебаркульский), Yurginsky (Юргинский) and Aleysky (Алейский), though some naval and coastal components will be held outside the Central District. While CSTO member states regularly join these exercises, China’s participation is new. In September 2018, 3,200 Chinese troops (two integrated armored battalions) joined the massive Vostok 2018 (East-2018) exercises (297,000 service members, 1,000 aircraft, 36,000 pieces of equipment, and 80 ships).

For Center 2019, all the personnel and equipment of the participating PLA will be transported to the Western part of Russia. In late August, the PLA had already moved its heavy equipment (Type 96 main battle tanks and Type 04 armored personnel carriers) by rail and it arrived in the Russian city Orenburg (Оренбург) on Sept. 4. It will be interesting to see if this westward movement of the PLA’s units will continue when PLA units appear in Russia’s Western exercises in the coming two years.

Between panda and bear: identity and status

The search for an appropriate definition of the “best” bilateral ties between Beijing and Moscow has been going on for some time. By the time of Xi’s visit to Moscow in early June, there was a rush, particularly on the China side, to offer competing assessments about the nature, scope, and limitations of the Russia-China relationship.

At the official level, Chinese State Councilor (国务委员) Dai Bingguo (戴秉国) said shortly before Xi’s visit that Sino-Russian bilateral ties had reached the state of a new type of major power relationship characterized as “the most normal (最正常), healthiest (最健康), most mature (最成熟) and most substantive (最有质量).” While the four-“mosts” depiction of bilateral relations was accompanied by the upbeat (“new age”) and even festival theme for the Putin-Xi summit, it may be part of the effort to counter a persistent sense of anxiety, particularly from the Russian side, that the steadily growing asymmetry of power between Russia and China would put Russia in a position of junior partner.

For some in Russia, Moscow has already become a “second fiddle” to Beijing. Even during this “best” era of bilateral relations, Russia’s China policy was said to have gone through a cycle: hoping to form a close alliance with China after the Ukraine/Crimea crises to disappointment in early 2019. Some Russian analysts believe that even if relations with China are getting closer, they benefit Beijing but not necessarily Moscow. These critical views of the relationship may not be part of the mainstream in Russia, but they never disappear even during the “best” times. Indeed, the “China threat” view may have gained enough ground in Russia to force Foreign Minister Lavrov to publicly dismiss it. “Attempts to promulgate the ‘Chinese threat’ myth can be traced back to those worried about the constructive development of the Russian-Chinese ties,” he said in an interview with Argumenty I Fakty Daily (Аргументы и факты) published in Moscow. Commenting on rumors that about 12 million Chinese people live in Russia’s Far East and Siberia regions, Lavrov said he doubted the accuracy of those figures, adding that concerns about the issue were “clearly exaggerated.”

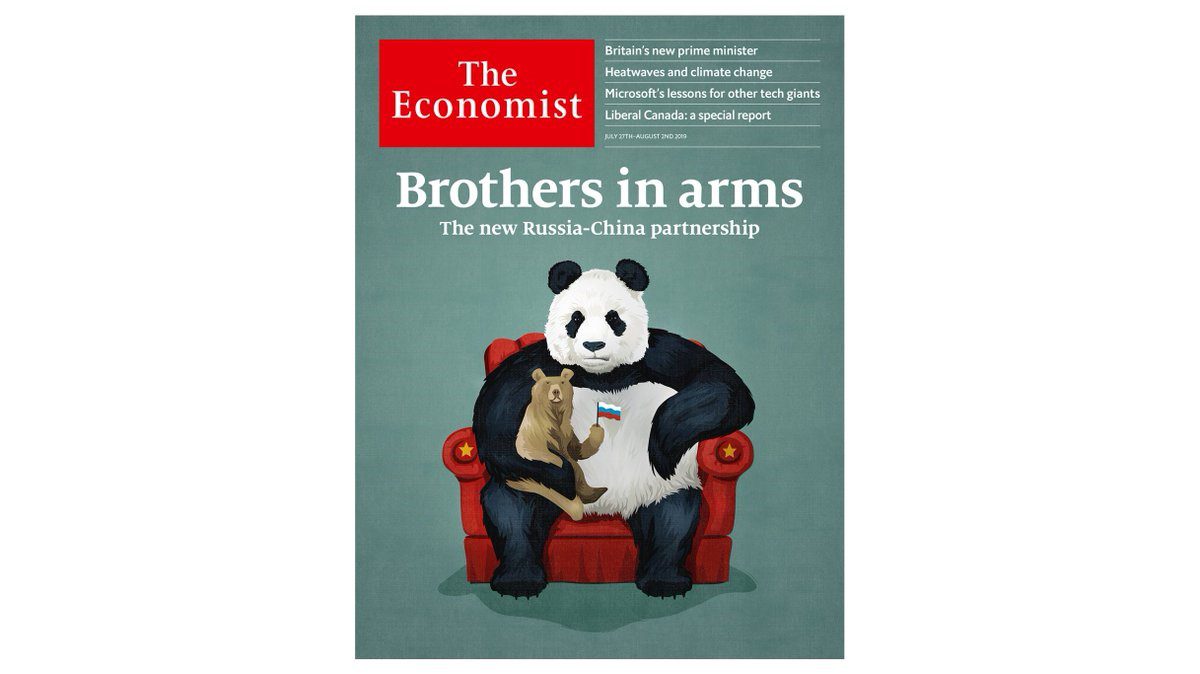

Russia’s concerns were noticed by Washington, which has tried to weaken the emerging “Beijing-Moscow axis” as much as possible. Western media, too, was eager to highlight the increasingly asymmetrical relationship between Beijing and Moscow in terms of power. The lead article of the Economist, for example, was titled “The Junior Partner: How Vladimir Putin’s embrace of China weakens Russia.” Its cover featured a gigantic giant panda (China) holding a teddy bear (Russia) on his lap.

The Economist’s cover depicts an asymmetrical relationship between China and Russia.

The panda-teddy image apparently had an impact on the public space. In early September, Lavrov responded that the Economist’s claim “should not characterize the relations between the two countries… which was about relations between sovereign states.” China, too, was apparently alarmed by the extent of Western efforts to lure Russia away. In his meeting with Russian President Putin following talks with Lavrov in early May, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi said that he hoped that “our relations are not vulnerable to obstruction or outside interference.”

Beyond the “best-ever” relationship: alliance, alignment, and autonomy

The Economist’s portrait of China-Russia ties may echo some Russian pessimists. It nonetheless missed a considerable part of the reality in China. Chinese strategists are keenly aware of Russia’s anxiety and hope Russia would be able to overcome current hurdles. This would not only improve Moscow’s status within China-Russia bilateral relations, but also within the China-Russia-US triangle, and lead to a more stable construct of relations among the three.

For many Chinese scholars and strategists, Russia’s role in both Chinese foreign policy and global balance of power did not diminish with the sharp decline of the Russian power in the post-Soviet decades. Russia’s considerably low GDP level was deceptive and did not reflect the country’s potential in both tangible and intangible ways, according to Zhang Deguang (张德广), a former ambassador to Russia. It has been the consensus in China that Russia needs to be respected, particularly when Russia is going through difficult times at home or abroad. China should not take advantage of Russia’s weakness. In a world of unpredictability and fluidity, Russia has regained considerable influence as an independent and stabilizing factor. With the rapid deterioration of China’s relations with the US under the Trump administration, China needs more from Russia than the other way around. As a result, Chinese analysts actively debated the nature, parameters, and future direction of a possible alliance relationship with Moscow, which culminated during Xi’s June visit to Russia.

At the extreme end of this discourse, Wang Haiyun (王海运), a former military attaché to Moscow, pushed for a fast track for the two militaries to develop closer relations. Short of a formal alliance, the two militaries should treat each other as “special friendly forces” (特殊友军) in which the two sides would further transparency in their strategic thinking for the sake of strategic mutual trust (战略互信). In operational terms, the two militaries should cover each other’s rear while facing external threats (军事部署上“背靠背”, 构成掎角之势). The two sides should also significantly increase their joint R&D projects.

Yan Xuetong (阎学通), a leading scholar of international relation in Beijing, believes that Russian strategists are rational and would always choose options to optimize and maximize Russia’s interests. In the foreseeable future, three factors would help Russia realize that allying with China is beneficial for Russia: continued US hostility toward both China and Russia, the steady rise of China’s military power, and China’s sincerity in cooperating with Russia. In operational terms, Yan envisioned an alliance with Russia focusing exclusively on “strategic security” (战略安全领域) without spilling into other issue areas such as economics, political system, religion, ideology, and environmental policies. What should be avoided is the Sino-Soviet alliance of the 1950s in which Russia tried to dictate domestic politics of China, leading to the breakdown of the alliance. At the international system level, a China-Russia alliance will be primarily defensive in nature (防御型同盟), unlike the expansionist Sino-Soviet alliance (扩张型同盟) of the past that sought to promote communism in the world. The sustainability of such an alliance depends on the acceptable baseline for Beijing and Moscow, that is, it is at least unharmful (至少无害) for the two large Eurasian powers. In the next 10 years and beyond, it is unlikely that Russia would drag China into a war with its neighbors that Russia could not manage by itself. In the last analysis, China has been defined as a threat for many years no matter what foreign policy posture China takes, be it low-profile (韬光养晦) or non-alliance.

Yan recalled that Russian President Boris Yeltsin proposed in 1999 an alliance with China, but Beijing did not reciprocate because of its non-alliance constraints. For this particular instance, Zhang Wenmu (张文木) in Beijing offered a significantly different interpretation of China’s non-alliance policy by arguing that the essence of China’s non-alliance posture is not necessarily not allying with any country but a policy of remaining independent. An independent foreign policy was more genuine than that of the non-alliance movement such as India in the 1950s. To put it differently, Deng believed that to ally or not ally with others was China’s independent right (独立自主的权利) and that it should not be compromised at will. China should decide when and how to move into alliance with others according to China’s own interests. Assessing current China-Russia ties, Zhang dismissed those who see Russia as an unreliable alliance partner. Nor should different political systems be an obstacle to deepening current strategic partnership.

The growing cry for an alliance with Russia, mostly among Chinese academics, is counter-balanced by those with more cautious views. Xie Chao (谢超), a young scholar in Beijing, argues against the alliance option – at least for the time being – for several reasons. First and foremost, n alliance between the second largest economic power and second largest military state embodied certain offensive implications. Such a revisionist strategy may lead to strong countermeasures from other major powers, leaving little room for the US.

Xie’s major reservation to the alliance option was that it was more China-centered while overlooking what Russia really wanted. For him, Russian strategic priority was Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) members, or the post-Soviet space. Meanwhile, relations with China were at best a mix of cooperation and competition. As a result, relations between the two had yet to reach the level of a joint anti-hegemonic alliance. In the security area, Western pressure on Russia was less than that on China. This means Moscow’s need for an alliance is less than China’s need. A Russia that does not ally with China in East Asia leaves more room for diplomacy and flexibility in the region. It is in Russia’s interest to preserve Russia’s economic relations with Europe and an alliance with China may reduce Russia’s space in its economic interaction with Europe. For both Russia and the US, bilateral relations may continue to be constrained in the foreseeable future. Limited cooperation, however, would remain an option for both. In the final analysis, Russia seeks a multipolar world, which would benefit it more than a world dominated by one or more hegemons, status quo or challenger. If this is correct, Russia can extract more from interactions with China when the US pursues a containment policy against China. Given these considerations, China needs to be clear that an ideal partnership is not an irreversible path toward alliance. Similarly, the end of the non-alliance posture is not a path toward alliance. Short of a formal alliance with Moscow, Xie recommended that China push for a more cooperative relationship with Moscow across the board, while retaining China’s strategic flexibility. If the threshold (临界点) of an alliance with Russia does arrive, China would not be unprepared.

Xie first voiced his argument in 2016 when Chinese policy and academic communities started to debate the alliance option. Since then, Xie articulated similar strategies on many occasions. His most recent piece was in Sohu.com, one of the most popular search engines in China, which may indicate that his view is reaching wider audiences. It also meant that the scope of the debate was getting wider and perhaps becoming more acceptable by China’s policy-making community.

In retrospect, the “new era” of the Sino-Russian relations is meant to explore the potential and new parameters of bilateral ties. Such an approach was systematically articulated by Zhao Huasheng, a senior Russia scholar at Fudan University in Shanghai. In a long paper published at the end of 2018, Zhao systematically spelled out the origins, dynamics, and outcomes of various types and shapes of triangle politics between China, Russia, and the US. He warned about the danger and cost of China moving toward alliance relations with Russia. The highest achievement of China’s diplomacy, according to Zhao, was to maintain friendly ties with both powers within the US-Russia-China triangle: China should avoid turning partners into enemies and the China-Russia partnership, not alliance, is the best mode (黄金模式). However, if US-China and US-Russian relations continued to deteriorate, China and Russia may be forced to enter into a quasi-alliance without formally declaring an alliance. Even so, such a “gentleman’s-agreement” (君子协定) would still allow considerable space for diplomacy; neither Beijing and Moscow would have to make hard choices (极化选择). China should rationally, effectively, and constructively engage in triangular politics for the sake of strategic stability.

The alliance discussion in China is not the only discourse regarding the three great powers, though it was the most visible and loudest. Scholars and analysts continue to explore the current “best-ever” relationship between Beijing and Moscow at historical and systemic levels. Feng Shaolei (冯绍雷), one of the most prominent Russologists in China, looked beyond an alliance discourse that was based on passive moves in reaction to external stimuli. Instead, he saw the “new age” as the outcome of a protracted experience of the two largest Eurasian powers in modern history. Peaceful coexistence and interaction between Russia and China is an indicator of a diverse world, which is an alternative to the civilizational clashes discourse in the West.

The world beyond Russia and China, however, continued to move rapidly as Washington opted to downgrade relations with Beijing and move toward what Niall Ferguson defined as “the early stages” of a second Cold War. For this British historian, a wider confrontation with China, which started in the form of a trade war, is assuming a life of its own and cannot be simply turned off by Trump.

Although Ferguson did not see the possibility of a hot war with China – such as in the South China Sea – leaders in Beijing have been surprised by the virtual freefall in US-China relations, plus the eerily casual talk by a top State Department official of so-called “civilizational clashes” with China. For Beijing and Moscow, the unpredictability of their relationship with Washington may be a bigger challenge than the actual grave state of affairs. The beautiful Xi-Putin relationship should not be overly celebrated.

April 29-May 4, 2019: Chinese and Russian navies conduct the second stage of their Joint Sea 2019 naval exercise in the Yellow Sea.

May 13, 2019: Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi visits Russia at the invitation of Russian counterpart Sergei Lavrov. They meet in Sochi and discuss international order, multilateral and bilateral cooperation in economics, security, military, etc. Russian President Putin meets both after their talks.

May 22, 2019: Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) Foreign Minister Meeting is held in Bishkek.

May 30-31, 2019: Russian Global Affairs Council and China’s Academy of Social Sciences jointly hold a conference in Moscow titled “Russia and China: Cooperation in the New Era for the 70th anniversary of Sino-Russian diplomatic ties.

June 5-7, 2019: Chinese Communist Party Chairman Xi Jinping visits Russia to attend the 23rd Saint Petersburg International Economic Forum (SPIEF) and celebrate the 70th anniversary of diplomatic ties.

June 13, 2019: Chinese Ground Forces Col. Gen. Han Weiguo visits Russia and meets Chief of Russia’s General Staff Army General Valery Gerasimov in Moscow.

June 14, 2019: SCO’s 19th summit is held in Bishkek. Chinese President Xi and Russian President Putin attend and join the fifth China-Russia-Mongolian meeting with Mongolian President Battulga on the sidelines.

June 15, 2019: Conference on Interaction and Confidence-Building Measures in Asia (CICA) holds its fifth summit in Dushanbe. President Putin and Chairman Xi join the summit and give a speech. CICA issues a joint declaration.

June 28, 2019: President Putin, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, and Chairman Xi meet in the Russia-India-China (RIC) format on the sidelines of the G20 Summit in Osaka.

July 12, 2019: Russia and 36 other states support China’s policies in Xinjiang in the UN.

July 17, 2019: A delegation from the Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC), which oversees national cyber policy, meets officials at Russia’s state communications watchdog in Moscow. Russian state telecoms watchdog Roskomnadzor says in a statement that it discussed cooperation with the Chinese and had agreed on further meetings in the future.

July 17, 2019: In an interview with Argumenty I Fakty daily (Аргументы и факты) in Moscow, Foreign Minister Lavrov says that China poses no threat to Russia.

July 23, 2019: Two Russian Tu-95Ms and two Chinese H-6K bombers jointly patrol a pre-planned route above the Sea of Japan and the East China Sea, “strictly in accordance with international law,” according to a Russian Defense Ministry statement. Both South Korea and Japan scramble military aircraft to ward off the bombers.

July 24, 2019: Tass reports that Russia will deliver a second S-400 surface-to-air missile system to China.

July 25, 2019: Taliban spokesman says that Russia and China would become guarantors of a peace agreement with the United States.

July 25, 2019: Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson says that China welcomes Russian concept of collective security in Persian Gulf.

Aug. 10, 2019: New Chinese Ambassador to Russia Zhang Hanhui arrives in Moscow.

Aug. 21, 2019: Russia and China request the United Nations Security Council to meet to discuss “statements by U.S. officials on their plans to develop and deploy medium-range missiles.”

Aug. 31, 2019: The sixth Session of the China-Russian Committee of Strategic Cooperation for Satellite Navigation is held in Kazan, Russia. The two sides agree to implement the cooperation accord between China’s Beidou and Russia’s GlONASS satellite guiding systems.