Authors

Yu Bin

YU Bin (于滨, Ph.D Stanford) is professor of political science and director of East Asian Studies at Wittenberg University (Ohio, USA). Yu is also a senior fellow of the Shanghai Association of American Studies, senior fellow of the Russian Studies Center of the East China Normal University in Shanghai, and senior advisor to the Intellisia Institute in Guangzhou, China. Yu is the author and co-author of six books and more than 150 book chapters and articles in journals including World Politics, Strategic Review, China and Eurasia Forum Quarterly, Asia Policy, Asian Survey, International Journal of Korean Studies, Journal of Chinese Political Science, Harvard International Review, Asian Thought and Society. Yu has also published numerous opinion pieces in many leading media outlets around the world such as International Herald Tribune (Paris), Asia Times, People’s Daily (Beijing), Global Times (Beijing), China Daily, Foreign Policy In Focus (online), Yale Global (online), Valdai Club, the BBC, Public Radio (USA), Radio Beijing, Radio Australia. Previously, he was a fellow at the Strategic Studies Institute (SSI) of the US Army War College, East-West Center in Honolulu, president of Chinese Scholars of Political Science and International Studies, a MacArthur fellow at the Center of International Security and Arms Control at Stanford and a research fellow at the Center of International Studies of the State Council in Beijing.

Articles by Yu Bin

China - Russia

May — December 2024Moscow and Beijing at the Dawn of A Grave New World of Trump 2.0

The election of Donald Trump as the 47th US president changed the chemistry between Washington, Moscow, and Beijing so much and yet so little. It was so much because the war-ending rhetoric of the president-elect was in sharp contrast to his predecessor’s steadfast support of Ukraine. It was so little because the war in Ukraine not only continued but even escalated after Trump’s decisive electoral win in early November as the Biden administration rushed arms to Ukraine with much relaxed restrictions (on ATACMS, etc.). Meanwhile, Beijing-Moscow relations continued to broaden and deepen throughout 2024 despite Trump’s repeated vows to split the Russia-China entente. Xi and Putin met three times in six months (May, July, and October). Their joint enterprises (SCO, BRICS, etc.) also expanded steadily while experiencing growing pains. Meanwhile, the two large powers considerably stepped up their mil-mil interactions with more exercises, exchanges, and joint patrols. It remains to be seen how Trump would operationalize his campaign rhetorics not just to capture a pivotal position within the Moscow-Beijing-Washington triangle, but more importantly, to avert the Kissingerian dark prophecy of a grave new world of WMD and AI racing toward World War III.

Putin 5.0 and Russia’s China-Pivot

In his first 2024 campaign rally in March 2023, Trump blamed Biden for the devastating war in Ukraine, “casual talk” about nuclear war with Russia, and a China-Russia unity to “carve up the world.” A year later, Putin won his fifth term and then found himself in China, the first foreign visit of his fifth term in the presidency. It was also his first official visit since the outbreak of the Ukraine War in February 2022 (his October 2023 trip was defined as a “working visit” for the annual BRICS summit). 2024 was also a time of the 75th anniversary of China-Russian/Soviet diplomatic ties.

Despite the war, Moscow and Beijing managed to maintain and even deepen their bilateral ties. This time, Putin brought with him almost the entire Russian government (except the prime minister) to China, including six deputy prime ministers and heads of various governmental departments (foreign affairs, defense, national security, finance, economics, nuclear power, aerial space, railroad, nuclear power, etc.). These senior officials and their staff, along with hundreds of Russian businesspeople, filled up more than 20 large aircraft.

In Beijing, Xi and Putin held several hours of “sincere and cordial meetings covering many topics.” A joint statement was issued after the meeting. The 10,000-word document stressed the principles of nonalignment and equality in bilateral relations for a world order of “multipolarity and democracy” (Part I). As two large powers who suffered the most in WWII, the two sides said they would strongly defend the post-WWII world order by opposing distortion of war history and any effort to revive Nazism/militarism.

Figure 1 Following the talks, Putin and Xi signed a Joint Statement. Photo: Sergei Savostyanov

The statement covers nine functional areas for cooperation: security (parts II, VII, and X), economics (III), societal exchange (IV), multilateralism including the UN, Shanghai Cooperation Organization, BRICS (V, VI), the environment (VIII), and Ukraine (IV). Part III on economics listed 20 sub-areas for cooperation including the “Bilateral Investment Cooperation Planning Outline” (pending), the key to China’s large investment in Russia. The document has two noticeable additions: setting up an Arctic route cooperation subcommittee and a trilateral dialogue with North Korea regarding Chinese vessels’ access to the sea via the lower reaches of the Tumen River. While the former would open much of the Russia-controlled northern sea route and port facilities to China, the latter would play a key role in revitalizing China’s northeastern provinces.

The bulk of the joint statement (three parts) was about security. Part II, for example, called for “steady development for defense cooperation for both regional and global security.” The two sides needed to “deepen mutual trust and coordination,” and expand joint exercises and joint naval/aerial patrol. Communication and dialogue at various levels should be enhanced, the statement read, as well as coordination in multilateral forums (UN, SCO, BRICS) for anti-terror, law enforcement, and emergency management coordination. Part VII highlighted the danger of nuclear war, proliferation, militarization of outer space, weak international regulations on chemical/biological weapons, AI, and US deployment of intermediate-range missiles in the Asia-Pacific.

The emphasis on security was further underscored in Parts V (UN), VI (regional forums), VIII (environment), and IV (Ukraine) in which security issues were considered paramount for a just and enduring security for all. Lengthy joint statements between the two sides are not uncommon. The tone of the document, however, indicated a much stronger and more direct criticism of Washington’s “unilateralism” and rule-breaking behavior across all issue areas.

Is it Still the Economy…

Despite the war, Russia remained the world’s 4th largest economy in 2023 in PPP terms, and 11th in nominal GDP. Meanwhile, massive Western sanctions on Russia led to a marked increase in Russia-China economic transactions. In 2023, bilateral trade reached $240 billion, up from $108 billion in 2020. While China’s import of Russia’s oil increased by 24% to 107 million tons, China’s 553,000 vehicles exported to Russia accounted for 49% of Russia’s auto market, up from 19% in 2022. Bilateral trade was “not only developing but also flourishing,” remarked Putin in his meeting with visiting Chinese Premier Li Qiang on Aug. 21.

At the 29th prime ministerial meeting in Moscow, Li and Russian PM Mikhail Mishustin conducted “a detailed discussion on the entire range of trade, economic and humanitarian cooperation issues.” Eighteen documents were signed, including one to upgrade the outline of an investment cooperation plan to be finalized by the yearend. For many Chinese business leaders, Russia’s domestic law and regulations for foreign investment were quite “complicated,” and the sweeping Western sanctions made it worse. A new version of the investment plan would facilitate China’s 86 large investment projects in Russia totaling $200 billion. While most of these projects would be in the “traditional areas” such as energy, transportation, agriculture, auto industry, and home electronics, Premier Li stressed the need to “explore new areas of technological and industrial cooperation,” including digital economy, biomedicine, green development, etc.

For decades, economic and trade relations were the weakest links between China and Russia, as both tried to integrate into the West-dominated global trading system. The Ukraine War and the tightening of their strategic space led to a marked broadening and deepening of their economic intercourse.

Moscow and Beijing had so far refrained from moving to a formal alliance. Yet for Washington, Zbigniew Brzezinski’s 1997 warning regarding the emergence of a dominant and antagonistic Eurasian power is now descending across the vast Eurasian continent. The potential for a “marriage,” convenient or not, between the world’s energy/raw material and manufacturing giants seemed “unlimited” in both geoeconomic and geopolitical terms.

Multilateralism to Go

One key area of China-Russian cooperation in 2024 was to manage the “growing pains” of the SCO and BRICS against the ever-changing and more complex world. Xi and Putin met twice on the sidelines of the annual summits of the SCO in Astana (July) and BRICS in Kasan (October).

In Astana, they agreed to enhance cooperation for regional security. While Xi called for more “strategic coordination,” Putin echoed that Russian-Chinese cooperation in global affairs served as “a main stabilizing factor.” Both vowed to strengthen the SCO for regional stability. Twenty-four agreements were inked, including a development strategy until 2035, several cooperation programs to combat terrorism, separatism, and extremism for 2025-2027, an anti-drug strategy for the next five years, and its corresponding action program. As for global issues, participants endorsed the “Initiative On World Unity for a Just Peace, Harmony and Development” proposed by Kazakhstan for a new, democratic, and equitable international order.

This global vision of the regional security group got an instant boost in Astana as Belarus officially ascended became the SCO’s 10th member. A few days after the Astana summit, more than 100 PLA special forces were airlifted to Belarus for an 11-day “anti-terrorist” exercise (code-named “Attacking Falcon 2024,” July 8-19) in areas close to Poland and Ukraine. Despite its label as anti-terrorist, it was carried out by the regular PLA unit from the 80th Group Army of the Northern Theater Command at the time of heightened tension between Belarus and Ukraine.

Despite these institutional gains, there was a growing gap between the SCO’s numerous adopted agreements/declarations and its ability to implement them, according to Professor Pan Guang, a prominent scholar on Central Asia in China. Part of the problem was SCO’s unanimity-based decision-making mechanism, which frequently led to inaction. SCO’s small and weak institutional setup (Secretariat in Beijing and the Regional Anti-Terrorist Structure in Tashkent, Uzbekistan), too, badly needs an update.

Perhaps more than anything else, Russia’s influence in Central Asia steadily declined largely because of its preoccupation with the Ukraine war. A case in point was the final agreement in June 2024 regarding the China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan (CKU) railroad that had been put on hold for 30 years by disagreement over its finance and Moscow’s hesitation. With a projected annual capacity of 15 million tons of cargo, CKU represents the shortest route between Shanghai and Paris. In the foreseeable future, Russia may have to live with a more proactive China in its traditional backyard. Alternatively, Washington and its allies will make further inroads into the post-Soviet space where de-Russianization was already irreversible.

More “Breaks” onto BRICS

As the SCO moved beyond its regional confine, BRICS also added more strategic and global dimensions. Putin and Xi met again in Kazan (Russia) prior to the BRICS group summit. Their “in-depth exchange of views on major international and regional issues of common concern” was described as “a key moment” of the annual summit, said Chinese FM Wang Yi. Both leaders spoke highly of the bilateral ties. While Putin described it as “a paradigm of how inter-state relations should be constructed,” Xi emphasized the principles of non-alignment, non-confrontation, and non-direction against third parties.

With the theme “Strengthening Multilateralism for Just Global Development and Security,” the Kazan summit was the first enlarged BRICS gathering with five new members (Iran, Egypt, Ethiopia, the United Arab Emirates, and Saudi Arabia). As BRICS’ rotating host, Russia organized more than 200 events. Thirty-six countries, including 22 heads of government/state and UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres, joined the annual gathering. BRICS Business Forum also attracted more than a thousand participants.

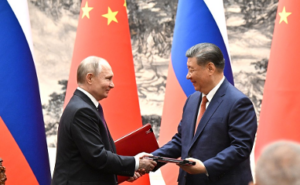

In his speech to the BRICS business forum, Putin noted that the 10-member group now had 46% of the global population, 36% of the world’s landmass, and 45% of oil output. But even before its expansion, BRICS had overtaken the G7 in PPP terms (37.4% vs 29.3%).

Figure 2 Illustration and Observation by Christian Taiushi MA UZH Source: Raw Data from IMF

The BRICS summit ended with the signing of the Kazan Declaration, a 134-clause document covering every conceivable area of global issues. The long document “is a declaration for a new global order,” according to Andrey Kortunov of the Russian International Affairs Council and Professor Zhao Huashen of Fudan University in Shanghai. BRICS did not merely add new members but was becoming a platform for the entire Global South, noted Kortunov and Zhao in a jointly penned article. Four areas of cooperation were emphasized: multilateralism (Articles 6-23), global/regional stability and security (Articles 24-56), economic/financial development (Articles 57-118), and societal exchange (Articles119-132). Of these areas, security and development were highly interdependent, noted Kortunov and Zhao.

Ukraine was briefly mentioned in Article 26, stressing the need to comply with the UN principles and make all efforts to end the conflict. The bulk of the security section dealt with conflicts and challenges around the world, particularly in the Middle East including the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, which reflected the views of the BRICS four new Islamic members (Iran, Egypt, the United Arab Emirates, and Saudi Arabia).

While multilateralism was a platform, the three functional areas of security, development, and cultural/humanitarian exchanges largely reflected the three “proposals” outlined by Chinese President Xi Jinping in the past few years for global development (2021), global security (2022), and civilizational dialogue and coexistence. This was also the theme of Xi’s speech in Kazan. China’s vision for the BRICS future, therefore, was largely accepted by its diverse members.

BRICS’ trajectory, however, was not to rival, but to parallel the existing global system dominated by the West. It does, however, serve the interests of the Global South, argued Kortunov and Zhao. At a minimum, BRICS’ highly diverse constituents are fundamentally different from the largely exclusive Western institutions such as G7, the European Union, and NATO, whose members are similar in political, economic, and cultural/religious construct. Hence the need for an interface for the diverse interests of its vastly different members.

Enhanced Mil-Mil Ties

In his meeting with Putin in Kazan, President Xi described the world undergoing “unprecedented tectonic transformation” and “serious changes and upheaval…unseen for centuries.” 2024 witnessed a significant increase in Russia-China mil-mil interactions. In July-September, for example, several large-scale joint exercises/operations even overlap with one another:

- July 2-16: Three Chinese naval ships and one Russian corvette conducted a 15-day joint patrol of the Western Pacific and the South China Sea, the fourth joint patrol since 2021.

- July 12-17: the annual (since 2012) “Exercise Joint Sea-2024” was held off the Zhanjiang naval port in southern China. Seven Chinese and Russian naval vessels joined the drill for “maritime security threats.”

- In late July, Chinese naval ships were present in both St Petersburg and Vladivostok for the 328th anniversary of the Russian Navy.

- July 24: Russian and Chinese strategic bombers carried out a joint patrol of Far East Russia and the Bering Sea near Alaska, the 8th strategic aerial patrol by the two militaries since 2019. For the first time, the joint patrol reached international airspace near Alaska.

August was quiet with only one military exchange: commander of the PLA Ground Forces Gen. Li Qiaoming led a delegation to the annual “Army-2024 Forum” outside Moscow. He held talks with Russian Ground Forces’ Commander-in-Chief Oleg Salyukov. By September, the high-frequency exercise mode returned:

- On Sept. 10-15, China launched the first phase of the annual “Northern/Interaction-2024” naval exercises with Russia. Unlike the 2023 series primarily in the Sea of Japan, the 2024 version extended to the Sea of Okhotsk which had been carefully guarded as an “internal sea,” or “Russia’s Great Lake,” by Soviet/Russian authorities since the end of WWII. The Chinese press referred to Russia’s “fortified waters” (堡垒海域) presumably for deploying Soviet/Russia’s strategic nuclear submarines for second/retaliatory strikes.

- On the same day (Sept.10), Russia began its “Ocean 2024” strategic command-and-staff exercises. Some 90,000 troops and more than 500 ships and aircraft drilled across the Pacific and Arctic Oceans, and the Mediterranean, Caspian and Baltic seas. China was the only country that participated in the exercise.

- The “recess” between the two phases of China’s “Northern/Interaction-2024” was not wasted. Between Sept. 16 and 20, Chinese and Russian coast guard ships held a joint drill near Peter the Great Bay off Vladivostok. This was followed by a first-ever joint patrol of the northern Pacific beginning Sept. 21. By Oct. 1, the patrol ships reached the Arctic Ocean, which was a first for the Chinese Coast Guard ships.

- No sooner had the Coast Guard ships departed from the northern Pacific than the second phase of the Northern/Interaction-2024 joint exercise began on Sept. 21. This was immediately followed by the 5th joint patrol of the northern Pacific by the same naval vessels of the two navies, which was the first time for the two sides to conduct two joint maritime patrols within one year.

The high frequency and intensity of the Sino-Russian interactions occurred against a backdrop of heightened tension in the West Pacific. From late June to early August, the US-led Rim of the Pacific 2024 exercises (RIMPAC 2024), the largest in the world, drilled around the Hawaiian Islands with 40 surface ships, three submarines, 14 national land forces, over 150 aircraft, and more than 25,000 personnel from 29 countries.

It was during the multi-nation “Sama Sama” exercises that the PLA launched a 13-hour massive Joint Sword-2024B drill around Taiwan on Oct. 14. The exercise was a simulated blockade of the island shortly after Lai Ching-te’s speech on Oct. 10 (ROC’s national day), which was deemed as “provocative and dangerous” and aimed toward nominal independence. On the same day, Russian Defense Minister Andrei Belousov traveled to Beijing and held talks with Chinese counterpart Dong Jun. Military cooperation between Russia and China was important in safeguarding global and regional peace and stability, said Belousov.

While exercises came and went, the US deployment of an intermediate-range missile system in Japan and the Philippines was considered a long-term grave threat to China and Russia. “[L]and-based intermediate-range missiles in the Asia-Pacific region will pose the biggest security threat to the region,” TASS cited PLA’s Lt. Gen. He Lei on Sept. 12. The 1987 Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty prohibited the deployment of intermediate-range missiles but Washington withdrew from it in 2019.

Amidst these heightened military activities in 2024 was China’s effort to elevate/demonstrate its nuclear capabilities, with or without Russian cooperation. On Sept. 25, China tested, for the first time in 44 years, an ICBM (DF-31AG with a range of 12,000 km) from Hainan Island to the South Pacific. To this, Russian Presidential Spokesman Dmitry Peskov remarked “[T]his is China’s sovereign right… We respect [this].” In the Nov. 29-30 ninth joint strategic aerial patrol with Russia, China dispatched, for the first time, two long-range H-9N strategic bombers with refueling capabilities for a combat radius of 6,500 km. The nuclear-capable bomber could carry YJ-12 supersonic antiship missiles, CJ-100 cruise missiles, and even an air-launched variant of the hypersonic (Mach 10) DF-21 anti-ship ballistic missiles (see photo below). Many in China viewed this as a crucial step toward China’s first credible and operational airborne strategic deterrence.

Figure 3 H-6N Bomber with Ballistic Missile Photo: Military Watch Magazine

Intensified China-Russian mil-mil interactions occurred when Russia continued to be bogged down on its western front. Its vast east and Pacific regions were increasingly exposed despite Putin’s 2023 declaration that “the Far East is Russia’s strategic priority for the 21st century.” Enhanced military interactions with China were therefore highly desirable given China’s growing military capabilities.

For the PLA, Russia remained the sole source of real combat experience regardless of Russia’s battle performance in Ukraine. At the operational level, interoperability between the two militaries in 2024 meant more access to each other’s facilities for refueling and resupply. In the case of the joint bomber patrols of the northern Pacific, the flying range was much shorter for China’s H-6 bombers to reach their intended area off Alaska as they took off from an airfield in northeast Russia. Some Chinese military experts were speculating that a shorter route via Russia’s Arctic air space would make China’s strategic bombers a more viable and flexible deterrent than PLA’s land and sea options.

Embracing Trump “Shock-n-Awe” 2.0

Although Putin remarked jokingly in early September that he wanted the Democratic candidate Harris to win, he was clearly avoiding comments on Trump’s win at the annual Valdai Forum on November 7. The Russian president nonetheless said Trump “impressed” him as a “courageous man” in “extraordinary conditions” (the assassination). Meanwhile, Trump’s words about ending the Ukraine conflict and improving relations with Russia “deserve attention.”

As to Trump’s repeated rhetoric of splitting the Beijing-Moscow partnership, Putin said that Russia would not team up with the US in dealing with China. Relations with China “have reached a historical high and are based on mutual trust, which is something we lack in our relations with other countries, above all with Western countries,” Putin replied to a question from Prof. Feng Shaolei, a top Russologist in China. He further suggested that “everyone would win and there would be no losers if the United States … treats both Russia and China by moving away from its double containment policy towards a trilateral cooperation framework.”

There were good reasons for Russia to be more careful with Trump’s huge win, given the highly charged US domestic chemistry and two assassination attempts against candidate Trump. “I believe he is still not entirely safe,” remarked Putin in late November. Meanwhile, Trump’s Cabinet picks reportedly received multiple threats against them. Even under the best circumstances, converting Trump’s campaign rhetoric into policies would be difficult.

While Russia could afford to adopt a wait-and-see posture regarding Trump, Beijing perceived Trump’s return with visible unease for at least four reasons. One was Trump’s solid record of “China-heavy-and-Russia-lite” in both words and deeds in the previous eight years. And there has been no indication of any deviation from that.

Second, Biden’s China policy, which was seen as bad enough—“endless trouble, endless frictions, and endless struggles” (麻烦不断 摩擦不断 斗争不断) according to Wu Xinbo, director of American Studies Center of the prestigious Fudan University in Shanghai—would have to be interrupted if not disrupted given the gathering of China hawks under Trump. In this “you-go-low-I-go-lower” “China race,” Taiwan and the South China Sea could be the next flash points between Washington and Beijing.

Third, the US trade war with China, which was started by Trump in 2018, will likely escalate rapidly, further disrupting the already fragile supply chains of the world trading system. In contrast to Russia’s raw-material-based economic structure (oil, gas, grain, etc.), China’s globalized production chains, extensive energy supplies, and trading/shipping networks are far more vulnerable to sanctions and disturbances than Russia even under normal circumstances.

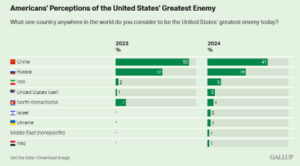

Last, a growing number of China’s foreign policy analysts came to see an eerily yet persistent “civilizational” factor permeating the Trump camp, in that white communism of the Soviet type and its post-Soviet variant were seen in a far more favorable light than “a great power competitor (China) that is not Caucasian” (words by Kiron Skinner, director of policy planning at the State Department during Trump’s first term). To China’s surprise and perplexity, Skinner herself is African-American. No matter how much Russia is demonized, Putin, and particularly his “healthy conservatism,” always has a strong appeal among conservative segments in the US/West. Such a sense of racial hierarchy may help explain why recent polls continuously show that more Americans view China as a greater enemy than Russia despite Russia’s war-prone propensity and China’s zero record of use of force in the past 45 years.

Figure 4 Americans’ Perceptions of of the United States’ Greatest Enemy. Photo: GALLUP

Moscow and Beijing, despite their long-term strategic partnership and being targets of Washington’s “dual containment” strategies, assume very different cultural/racial identities in the US domestic scene. It remains to be seen how far this genre of US identity politics will find its way to policies toward Moscow and Beijing under Trump 2.0.

End the War or the World?

Trump made his historic comeback a year after the passing of Henry Kissinger in November 2023. In their 2017 meeting in the White House, Trump described his “long-time” friend (Kissinger) as “a man of immense talent, experience, and knowledge.”

Despite the huge difference between the world’s most powerful salesman and the realpolitik thinker/practitioner, both men showed strong aversions to the Ukraine conflict. That said, the biggest difference between them is how the conflict may end. For more than six months, Trump repeatedly promised to end it in 24 hours.” Kissinger, however, warned that ending a conflict was far more difficult than starting one. “The test of policy is how it ends, not how it begins,” argued Kissinger shortly after the 2014 Crimea crisis.

For Beijing, the Trump-Kissinger discourse, regardless of the outcome, would put China between a rock and a hard place. As a profoundly conservative country, the ending of the Ukraine war, or any war, is good for China’s sprouting business around the world, particularly its Belt and Road Initiative now in its second decade with more than 150 countries. Such a prospect, however, would divert more attention and resources to America’s “China issue.”

Regardless, the Ukraine war was moving steadily toward a breaking point in the waning days of the Biden administration. On Nov. 17, Biden authorized Ukraine to use long-range ATACMS missiles (300-mile range) for deeper strikes into Russia, which Ukraine did two days later. On the same day, Putin approved changes to Russia’s nuclear doctrine. Now an attack from a non-nuclear state, if backed by a nuclear power, would be treated as a joint assault on Russia. On Nov. 21, the Ukrainian city Dnipro was struck by Russia’s newest nuclear-capable intermediate-range hypersonic (Mach 10) ballistic missile code-named Oreshnik (or “Hazel Bush”) with six independently-guided warheads.

Moscow and Beijing reacted very differently to this escalation. For Russia, it was “a qualitatively new round of escalation of tensions and a qualitatively new situation…in this conflict,” remarked the Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov. Meanwhile, Beijing urged all sides to de-escalate and find a political solution. The strongest reaction came from Trump’s supporters who almost unanimously depicted the ATACMS reversal as an “escalation move” toward WWIII. “It’s another step up the escalation ladder and nobody knows where this is going,” said Trump’s incoming national security adviser, Florida Rep. Mike Waltz.

Just a few days after Biden’s ATACMS decision, the New York Times reported that some officials of the Biden administration floated the idea of returning nuclear weapons to Ukraine as a deterrent against Russia. Although this was dismissed a few days later by National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan, the 21st-century version of the 1983 made-for-TV film The Day After was rapidly unfolding as Newsweek published a series of simulated impacts of nuclear blasts on major metropolitan centers in Europe, North America, Russia, China, and North Korea.

Russia’s reaction, or lack of reaction, to the Newsweek extravaganza may be uncharacteristic. Or it was exactly what Russia wanted. In contrast, China’s netizens erupted with disbelief and anger at Newsweek’s “coldblooded calculation” “reducing the untold human cost to lifeless statistics.”

For incoming US President Donald Trump ending the war in Ukraine is now a far more complex and difficult, if not impossible, issue. Meanwhile, time is limited for Trump, and perhaps for all other world leaders, to avert what Henry Kissinger warned, 11 months before his passing, was a global catastrophe (WWIII) in a grave new world of WMD and AI.

China - Russia

January — April 2024“March Madness” in Moscow and Beyond…

The concert hall massacre near Moscow on March 22 was a source of shock and awe for Russia and the world. The incident, which resulted in the deaths of 144 people and 551 wounded, was the largest since the 2003 Beslan school siege (where more than 330 hostages died). Its timing cast a long shadow over major developments in the first few months of 2024, particularly the fifth term of President Vladimir Putin, who won 87.28% of the vote just five days prior. It also made any effort to end the two-year Ukraine war more difficult, if not impossible. As a result, much of China’s mediation 2.0 (March 2-12) was in parking mode. The Sino-Russian strategic partnership, too, was tested by two different priorities: Moscow’s need for more security coordination on one hand and China’s interest in stability in the bilateral, regional, and global domains on the other. Whatever the outcome, the stage was set for more dynamic interactions between the two large powers in the months ahead.

China - Russia

September — December 2023From Geopolitics to Geoeconomics

In the last months of 2023, China and Russia increasingly prioritized economics and geoeconomics in their bilateral interactions. In the post-COVID era and with a virtual standstill in the Russian-Ukraine war, both sides searched for new growth potential in domestic, bilateral, and multilateral domains. In October, Russian President Putin visited Beijing for the 3rd Belt and Road Forum (BRF), which was attended by thousands of participants from 151 countries. It was a convenient occasion for Putin to expand his diplomacy, which had been considerably strained by Western sanctions since early 2022. Putin’s lengthy meetings (formal talks, a working lunch, and a “private tea meeting”) took almost half a day for the two-day BEF. Ten years after Xi’s launch of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), both sides found it necessary to adjust their policies between the increasingly globalized BRI and Russia’s regional grouping, the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU).

China - Russia

May — August 2023Testing the Limits of Strategic Partnership

In the summer months, both the upper and lower limits of the China-Russia strategic partnership were put to considerable tests. In the West, China’s peace-probing effort continued despite virtual stalemate in the Ukraine war and its sudden twists and turns (drone attacks on the Kremlin and Wagner mutiny). Beijing treaded carefully in restoring relations with Kyiv with the new Ukrainian ambassador in place. In the East, Russian and Chinese militaries conducted a series of aerial and naval exercises/operations with unprecedented scope and closer interoperability for almost three months (from early June to late August), something not seen even at the peak of the Sino-Soviet alliance in the 1950s. All of this occurred against the backdrop of increasingly hardened US-led alliance networks both in Indo-Pacific and beyond.

China - Russia

January — April 2023War and Peace for Moscow and Beijing

Perhaps more than any other time in their respective histories, the trajectories of China and Russia were separated by choices in national strategy. A year into Russia’s “special military operation” in Ukraine, the war bogged down into a stalemate. Meanwhile, China embarked upon a major peace offensive aimed at Europe and beyond. It was precisely during these abnormal times that the two strategic partners deepened and broadened relations as top Chinese leaders traveled to Moscow in the first few months of the year (China’s top diplomat Wang Yi, President Xi Jinping, and newly appointed Defense Minister Li Shangfu). Meanwhile, Beijing’s peace initiative became both promising and perilous as it reached out to warring sides and elsewhere (Europe and the Middle East). It remains to be seen how this new round of “Western civil war” (Samuel Huntington’s depiction of the 1648-1991 period in his provocative “The Clash of Civilizations?” treatise) could be lessened by a non-Western power, particularly after drone attacks on the Kremlin in early May.

China - Russia

September — December 2022Ending the War? Or the World?

As the Ukraine conflict was poised to expand, the “extremely complicated” situation at the frontline (in Vladimir Putin’s words on Dec. 20) gave rise to intensified high-level exchanges between Moscow and Beijing as they searched for both an alternative to the conflict, and stable and growing bilateral ties. As the Ukraine war dragged on and mustered a nuclear shadow, it remained to be seen how the world would avoid what Henry Kissinger defined as a “1916 moment,” or a missed peace with dire consequences for not only the warring parties but all of civilization.

China - Russia

May — August 2022Embracing a Longer and/or Wider Conflict?

Unlike in 1914, the “guns of the August” in 2022 played out at the two ends of the Eurasian continent. In Europe, the war was grinding largely to a stagnant line of active skirmishes in eastern and southern Ukraine. In the east, rising tension in US-China relations regarding Taiwan led to an unprecedented demonstrative use of force around Taiwan. Alongside Moscow’s quick and strong support of China, Beijing carefully calibrated its strategic partnership with Russia with signals of symbolism and substance. Xi and Putin directly conversed only once (June 15). Bilateral trade and mil-mil ties, however, bounced back quickly thanks to, at least partially, the “Ukraine factor” and their respective delinking from the West. At the end of August, Mikhail Gorbachev’s death meant so much and yet so little for a world moving rapidly toward a “war with both Russia and China,” in the words of Henry Kissinger.

ROUNDTABLE

June 13, 2022Flashpoints in the Indo-Pacific Following the Russian invasion of Ukraine

China - Russia

January — April 2022Ukraine Conflict Déjà Vu and China’s Principled Neutrality

Perhaps more than any month in history, February 2022 will come to symbolize how the states of peace and war can flip-flop in a few days, with dire consequences for the global order. On Feb. 21, just one day after the closing ceremony of the Beijing Winter Olympics, Russia announced its official recognition of the independence of the two breakaway regions (Donetsk and Luhansk) of Ukraine. Three days later, Russia launched its “special military operation” in Ukraine to end the “total dominance” and “reckless expansion” of the United States on the world stage (in the words of Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov). As the West imposed sanctions on Russia and rushed arms into Ukraine, China carefully navigated between the warring parties with its independent posture of impartiality.

China - Russia

September — December 2021Not So Quiet in the Western Pacific

For Moscow and Beijing, relations with Washington steadily deteriorated toward the yearend. This was in sharp contrast from early 2021 when both had some limited expectations for relaxed tensions with the newly inaugurated Biden administration. For Russian President Vladimir Putin and his Chinese counterpart Xi Jinping, each of their meetings (real and virtual) with Biden was frontloaded with obstacles: US sanctions, a boycott of the 2022 Winter Olympics, and screw-tightening at strategic places (Taiwan and Ukraine). Biden’s diplomacy-is-back approach—meaning US-led alliance-building (the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue and AUKUS for China) or reinvigorating (NATO for Russia)—turned out to be far more challenging than Trump’s erratic go-it-alone style. It was against this backdrop that China and Russia enhanced their strategic interactions in the last few months of 2021, particularly mil-mil relations at a time of rising tensions in the western Pacific.