Articles

US - Japan

US - Japan

May — December 2024Once Again, Leadership Transitions Challenge US-Japan Alliance

2024 closes with new governments primed to lead in the US and Japan. A surprise decision by Prime Minister Kishida Fumio to step away from leadership of his party in August led to an unprecedented race to succeed him. Nine members of the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) fought for the chance to become president of the LDP on Sept. 27, and in a surprisingly tight race, Shigeru Ishiba won the honor and thus became the 102nd prime minister of Japan on Oct. 1. Within days, Ishiba called a Lower House election for Oct. 27. The LDP lost dramatically, and in the Nov. 11 vote in the Diet, Ishiba’s LDP and its partner Komeito formed a minority coalition government. The US similarly was in the throes of political contest. On Nov. 5, Donald Trump won a decisive victory in the presidential election, and in the days that followed, the Republicans were declared winners in both the House and the Senate as well.

While Trump’s inauguration will not be until January 2025, his transition team began immediately to announce candidates for his Cabinet and for the many political appointments needed to fill out his new administration. There was little doubt that this would be a far more robust challenge to the status quo than Trump marshaled during his first term.

The US-Japan alliance continues to be a fundamental feature of US strategy in the Indo-Pacific. The bilateral agenda for strategic coordination has grown considerably, and significant changes in Japanese defense preparedness are underway. US forces, too, are adapting to the needs of the growing military imbalance in the region. Trilateral US-Japan-South Korea security ties have deepened, and a new trilateral with the Philippines seems promising. Across the region and globally, the US and Japan have joined in broader coalitions of strategic cooperation. And yet, there is concern that this burgeoning agenda of strategic cooperation could flounder as domestic priorities take center stage in both Washington and Tokyo.

A Fall Full of Elections

The fall brought national elections in both Japan and the US, though under notably different circumstances. In Japan, a snap election came as a surprise, following Prime Minister Fumio Kishida’s resignation, the subsequent LDP leadership race that elevated Shigeru Ishiba to power, and Ishiba’s abrupt decision to dissolve the Lower House. In contrast, the date of the US election may have been fixed and known, but the political landscape otherwise offered little predictability. President Joe Biden’s late decision not to seek reelection paved the way for Vice President Kamala Harris to step in as the Democratic nominee, only for former president Donald Trump and the Republicans to reclaim not only the presidency but also control of both the House and Senate.

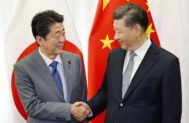

Figure 1 Prime Minister Fumio Kishida and U.S. President Joe Biden shake hands at the White House on Friday. Photo: Masanori Genko / The Yomiuri Shimbun.

On Aug. 14, Prime Minister Kishida announced that he would not run for reelection in September’s LDP leadership race, setting the stage for a fiercely contested and unusually open competition. The race initially featured nine candidates but quickly narrowed to three frontrunners: Koizumi Shinjiro, who would have been Japan’s youngest prime minister; Takaichi Sanae, vying to become the first female prime minister; and Ishiba Shigeru, a seasoned politician marking his fifth bid for party leadership. Ishiba consistently led public opinion polls, reflecting strong grassroots support, but he had long struggled to win backing from fellow Diet members. In the Sept. 27 election, Takaichi emerged as the top candidate in the first round of voting, but in the second round, Ishiba narrowly secured victory. His unexpected win highlighted divisions within the LDP but also marked an effort among some members to turn the page on recent scandals and rebuild public trust.

On Oct. 1, Japan’s parliament formally elected Ishiba as prime minister. Just over a week later, on Oct. 9, Ishiba surprised many by calling a snap election for Oct. 27, a move that appeared aimed at capitalizing on his initial popularity, taking advantage of a fragmented opposition, and securing a stronger mandate for his leadership. However, the gamble backfired. On Oct. 27, voters handed the ruling coalition of the LDP and its junior partner Komeito a decisive defeat. The LDP lost power for the first time in 15 years. While the Constitutional Democratic Party of Japan (CDPJ), led by former Prime Minister Yoshihiko Noda, gained significantly, much of the attention was drawn to the unexpected rise of the Democratic Party for the People (DPP) and its leader Tamaki Yuichiro, whose strong performance underscored the shifting political landscape.

The failure of any party or coalition to secure a majority of seats in the Lower House left uncertainty about the shape of Japan’s next government. On Nov. 11, Prime Minister Ishiba won a parliamentary vote to remain in office, making him the leader of Japan’s first minority government in three decades. Governing without a legislative majority presents significant challenges. The opposition now controls key committees, including the influential Budget Committee, which could complicate efforts to secure funding for next year’s priorities. Public approval of Ishiba’s Cabinet remains low, though it has improved slightly from 32% in late October to 40% in mid-November, according to Kyodo polling. Questions abound about how Ishiba will navigate this precarious political environment, including the extent to which smaller parties like the DPP will influence his policy agenda. With Upper House elections looming in July 2025, Ishiba’s ability to maintain leadership and deliver results will be closely watched, both at home and abroad.

In the US, the 2024 election campaign began with an air of familiarity, as it initially appeared to be shaping up as a rematch of 2020 between Biden and Trump. On July 15, the Republican Party officially selected Trump as their presidential nominee, alongside Senator JD Vance (Ohio) as his running mate. Trump had been the presumptive nominee since March 12, when he secured enough delegates in the Republican primary race. Despite unprecedented challenges—including his conviction on May 30 for 34 felony counts of falsifying business records to cover up a sex scandal tied to his 2016 campaign—Trump solidified his hold on the party. His path to the nomination was further punctuated by two assassination attempts, the most prominent of which occurred just days before the Republican National Convention. On July 13, Trump was shot and wounded in his right ear during a public appearance but was released from the hospital shortly thereafter and attended the convention as scheduled. A second attempt on Sept. 15 in Florida, while Trump was golfing, was thwarted before the would-be assassin could get close to him.

As the incumbent, President Biden initially appeared to have a clear path to securing the Democratic Party nomination, facing no primary challengers. However, his performance in the first debate on June 27 raised serious concerns among voters and within his party. Biden appeared visibly unwell, with a strained voice and moments of hesitation that cast doubts about his age and ability to serve another term—despite being less than four years older than Trump. These concerns quickly translated into declining public support and growing unease among Democratic leaders. On July 21, Biden announced he would not seek reelection, citing the need for new leadership and endorsing Vice President Kamala Harris as the party’s nominee.

On Aug. 2, Vice President Kamala Harris officially secured the Democratic nomination at the party’s national convention, becoming the first woman of color to lead a major party’s presidential ticket. Four days later, she announced Minnesota Gov. Tim Walz as her running mate, a choice seen as an effort to balance the ticket with a Midwestern governor who had garnered bipartisan support in his state. Initial polling suggested strong public enthusiasm for Harris, with many Democratic voters rallying behind her historic candidacy and optimism about her chances in the general election.

However, the Nov. 5 election saw Donald Trump ultimately emerge victorious, defeating Harris by a vote margin of 312 to 226 in the Electoral College. Trump carried all the key swing states, including Pennsylvania, Michigan, and Wisconsin, flipping several districts that had narrowly supported Biden in 2020. Nationwide, most areas showed a pronounced shift toward the right. The Republican Party not only reclaimed the presidency but also gained control of both the House and Senate, signaling a significant shift in American politics.

Looking ahead to US-Japan relations in 2025, new teams in both countries will take the lead in managing the alliance. In Japan, Prime Minister Ishiba, a former defense minister, has signaled his focus on defense by appointing four former defense ministers to key posts, including Takeshi Iwaya as foreign minister and Gen Nakatani as defense minister. On the US side, Trump’s cabinet nominees reflect a mix of experience and controversy. Senator Marco Rubio of Florida has been nominated for secretary of state, while former Army National Guard officer and Fox News host Pete Hegseth is Trump’s choice for secretary of defense. Rubio’s nomination is expected to sail through Senate confirmation, but Hegseth’s has drawn significant scrutiny over past allegations of sexual misconduct, excessive drinking, and financial mismanagement.

These new teams will inherit a complex and demanding alliance agenda, spanning bilateral priorities, regional security challenges, and pressing global issues.

The US-Japan Security Agenda

Bilateral security cooperation is burgeoning. Japan’s security review in 2022 produced a massive increase in security-related investments, including new conventional strike capability, improved operational integration and readiness for the Self Defense Force, and a new program of overseas security assistance. In January, the Japanese government agreed to purchase 400 land-based Tomahawk missiles, and in April, the Maritime Self Defense Force began training for their use. Deployment is expected in Japanese fiscal year 2025, which begins in April 1, a year earlier than originally planned.

Figure 2 South Korea, the US and Japan began their first trilateral multi-domain exercise on June 27, 2024, the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) said, amid efforts to deepen security cooperation against threats from North Korea, recently emboldened by its deepening ties with Russia. Photo: Yonhap

A new Joint Permanent Operational Command will also be stood up in the coming fiscal year, a first for Japan’s three branches of armed forces. This will integrate Japanese military operations to respond jointly to aggression and will place a single combatant commander in charge of Japan’s military readiness. To match this Japanese move to enhance operational integration, the US Forces Japan will gradually match operational requirements to provide smooth integration of operations between Japanese and US forces.

Finally, the Japanese government has begun to provide overseas security assistance to its neighbors in an effort to enhance their capacity to meet the growing instability in the region. By the end of the Japanese fiscal year 2023, this assistance included support for surveillance, radar, and patrol boats provided to the armed forces of the Philippines, Malaysia, Bangladesh, and Fiji.

All told, the Japanese government committed to enhancing its spending to 2% of GDP by 2027 when the current five year build up plan will be complete. In its third year, the plan will require consistent revenue if it is to be successful. A new defense tax is under consideration in the Diet, and preliminary cooperation between the LDP, DPP, and Ishin no Kai has been reached.

The US has also led efforts to institutionalize trilateral military cooperation between the Japanese, South Korean, and US forces in multidomain exercises named Freedom Edge. These were initiated after a bilateral Japan-South Korean defense agreement was reached in June at the Singapore gathering of the IISS Shangri-La Dialogue. Two of these trilateral exercises have been held since then, one in June and another in November, bringing the air, maritime, and space forces of all three allies together for a combined exercise dedicated to cooperation in case of a contingency on the Korean peninsula.

Keeping the US and Japan in Regional and Global Alignment

Much of the bilateral effort over the past several years has been focused on building coalitions of like-minded countries to cope with the growing challenge to the rules-based order. Two sets of relationships were emphasized by the Biden Administration. The first was the recovery of the Japan-South Korea bilateral relationship and the strengthening of institutionalized trilateral cooperation between the US and its two northeast Asian allies. Consultations between National Security Advisors, Joint Chiefs of Staff, and Intelligence heads bolstered a shared vision of strategic cooperation. Presidents Yoon and Biden and Prime Minister Kishida also committed to a set of shared strategic principles, outlined in the Spirit of Camp David joint statement in 2023, that were then amplified in November 2024 in a second leader’s meeting with Prime Minister Ishiba attending on the sidelines of the APEC meeting in Peru. In addition to the regular trilateral military exercises, noted above, the three leaders agreed to create a secretariat designed to facilitate trilateral cooperation.

Figure 3 US President Joe Biden hosted Australia’s Prime Minister Anthony Albanese, India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Japan’s Prime Minister Fumio Kishida for the latest summit of the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (Quad) in Wilmington, Delaware on September 23, 2024. Photo: South China Morning Post

Second, Japan and the US worked closely on building stronger ties among the Quad nations: US, Japan, Australia, and India. Leaders’ summits began in 2020 virtually but then became annual in-person meetings in 2021. In 2024, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese joined Japanese Prime Minister Kishida in Wilmington, Delaware to honor President Biden’s support of the Quad. A full agenda of Quad projects has developed over time, largely focused on aiding the Indo-Pacific nations in the provision of healthcare, infrastructure development, maritime domain awareness, and other collective goods required for regional stability. India is expected to host the 2025 Quad Leaders meeting.

Of course, concerns loom large over the fate of Taiwan. The US and Japan will continue to consult on the increased Chinese military exercises around Taiwan. Much of this is interpreted as pressure on President William Lai Ching-te. For example, a recent surge of Chinese military activity around Taiwan occurred shortly after Lai’s first overseas trip, which included visits to Pacific Island nations and transit stops in Hawaii and Guam—moves that were widely expected to elicit a strong response from Beijing.

But the growing assertiveness of China’s military beyond the Taiwan Straits continues to prompt enhanced security cooperation among US, Japanese, and other national forces. Chinese maritime pressure on the Philippines has also grown, challenging their maritime defenses and drawing a US restatement of its commitment to the US-Philippine alliance. During his fourth visit to the Philippines in November 2024, Secretary of Defense Austin announced the establishment of an information sharing agreement with the Philippines, designed to enhance the ability of the US and the Philippines to have real-time information on the activities of Chinese forces. Over the course of 2024, the PLA Navy has also increased its activity in and around Japanese waters, and Chinese-Russia strategic exercises have also increased. In August, Chinese government survey vessels intruded repeatedly into Japanese waters.

Conclusion

As the Ishiba Cabinet seeks to navigate its difficult position in the Japanese Diet, a second Trump Administration prepares to take the reins in the US. Trump’s Cabinet picks have created controversy already, and there is a sense that a major shakeup is coming to Washington. How this will affect US foreign policy remains to be seen, and personnel responsible for the day-to-day management of US Asia policy have yet to be identified. On the surface, however, there is little to suggest that the US-Japan alliance will suffer from a second Trump Administration.

Two issues will likely be of deepest interest to alliance watchers. The first is President-elect Trump’s position on tariffs and on trade more broadly. His announcement after his electoral victory that he is looking to place 25% tariffs on Canada and Mexico and “an additional 10% tariff, above any additional tariffs” on China will, of course, have spillover effects for many countries. Japan’s automakers have a stake in however the Trump Administration seeks to revamp the USMCA trade agreement, up for review in 2026. More short term, the political hot potato of the purchase of US Steel by Nippon Steel will be determined by the CFIUS decision expected on Dec. 18. President-elect Trump has stated he will reject the deal.

Figure 4 Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida meets with U.S. President Joe Biden and other Group of Seven leaders at NATO Headquarters in Brussels in March. Photo: REUTERS

Burden-sharing will also likely be on the agenda for the US-Japan alliance, as it will for the NATO allies. Already, there are rumors that the NATO commitment to spending 2% of GDP on defense might be raised to 3% in a new Trump administration, again with possible spillover effects for US Indo-Pacific allies. The five-year Host Nation Support agreement between the US and Japan is set to expire in 2027 and thus will need to be renegotiated during the next administration.

But it is likely the larger questions of US strategy under the Trump administration that will be of most concern. Three foreign policy areas are particularly important for Japan. First, US strategy toward China will be of deepest import to Tokyo. Given that Japan has identified China as its gravest strategic threat, Washington’s choices and how much Japan’s interests will be considered in those choices are paramount. Second, how the US decides its role in Ukraine and in the larger context of European security remains to be seen. Japan has committed extensive resources to Ukraine and to the effort to rebuild the nation. Similarly, Japan, like other G7 nations, has imposed sanctions on Russia, drawing retaliation from Moscow. Finally, Japan has a deep stake in the global economy and relies on a free and open global order. A retreat to mercantilist practices would have devastating effects on Japan’s future economic prosperity. Of course, the LDP will face yet another election next year, and Prime Minister Ishiba will have to juggle pressures from within to keep on top of the domestic dynamics at play in Tokyo even as he seeks to ensure a strong US-Japan partnership under a second Trump Administration.

US - Japan

January — April 2024Washington Welcomes Prime Minister Kishida

2024 began with a full agenda for the US and Japan. All eyes were on the January presidential election in Taiwan, and China’s reaction to it. The choice of William Lai Ching-te, who is currently vice president, cemented the hold of the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) on power, with a third term for the party. Lai has close ties with Japan and has made no bones about his expectation that Japan, as well as the US, will figure prominently in his hopes for Taiwan’s future. The invitation to former Kuomintang (KMT) President Ma Ying-jeou to visit Beijing on April 10 made it clear that Beijing had a different preference than the people of Taiwan. The uptick in Chinese military pressure across the Strait as well as in the South China Sea also concerned the US and Japan. The People’s Liberation Army’s growing demonstration of pressure on Taiwan’s eastern islands continued in the months after Lai’s victory, as Taiwan prepared to inaugurate him as president on May 20. The US and Japan found common cause also in speaking out against China’s growing aggression against Philippine maritime forces at Second Thomas Shoal.

US - Japan

September — December 2023As Good as it Gets?

The US-Japan relationship may well be at its all-time best. Animated by a concordance of vision and interests, the two governments are closely coordinating across a wide range of issues in a variety of venues—bilateral and multilateral, political, economic, and military. Concern about the potential destabilizing effects of regional developments provides considerable motivation for the two to work together. The final reporting period of 2023 provided ample evidence of their convergence. If that past is prologue, the year ahead should be a good one. Unfortunately, however, the tide could be turning. A political funds scandal has ensnared Japan’s ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), and the approval ratings of the government of Prime Minister Kishida Fumio are plummeting as a result. Even if the prime minister survives the scandal—and most indications are that he will—he will be tarred and distracted as the region and the world face new and mounting challenges.

US - Japan

May — August 2023A Busy Diplomatic Calendar for Biden and Kishida

2023 is the year for the US and Japan to intensify their cooperation in multilateral venues. The first opportunity was the G7 meeting in Hiroshima in May, and the last will be the APEC meeting in San Francisco in November. In between, partners were hosting other important meetings: the NATO Summit in Lithuania and the G20 in India. Across these meetings, Russia’s war in Ukraine has stayed at the top of the agenda. The war has focused attention on the rules-based order, but global economic cooperation was not far behind. Prime Minister Kishida Fumio traveled to Africa and the Middle East to offer assistance for food insecurity and to stabilize energy markets, while President Joe Biden reached out to nations in the Indo-Pacific, including Pacific Island nations and Vietnam, to deepen strategic cooperation. China continues to loom large. The Biden administration sent three Cabinet members to Beijing for long sought consultations. Secretary of State Antony Blinken finally realized his planned trip on June 18-19. Secretary of the Treasury Janet Yellen followed on July 6-9 to meet with her counterpart, Vice Premier He Lifeng.

US - Japan

January — April 2023The US and Japan Build Multilateral Momentum

2023 brings a renewed focus on the US-Japan partnership as a fulcrum of global and regional diplomacy. With an eye to the G7 Summit in Hiroshima in mid-May, Prime Minister Kishida Fumio began the year with visits to G7 counterparts in Europe and North America. Later in the spring, he toured Africa in an effort to gain understanding from countries of the Global South. The Joe Biden administration looks ahead to a lively economic agenda, as it hosts the APEC Summit in November on the heels of the G20 Summit in New Delhi in September. National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan laid out in detail the economic ambitions of the Biden national strategy on April 27, giving further clarity to how the administration’s foreign policy will meet the needs of the American middle class. Regional collaboration continues to expand. Both leaders will gather in Australia on May 24 as Prime Minister Anthony Albanese hosts the third in-person meeting of the leaders of the Quad. Also noteworthy in this first quarter of 2023 is the progress in ties between Japan and South Korea.

US - Japan

September — December 2022Ramping Up Diplomacy and Defense Cooperation

In the wake of the death of former Prime Minister Abe Shinzo, the fall brought unexpectedly turbulent politics for Prime Minister Kishida Fumio. In the United States, however, President Joe Biden welcomed the relatively positive outcome of the midterm elections, with Democrats retaining control over the Senate and losing less than the expected number of seats in the House. Diplomacy continued to be centered on various impacts of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, but both Biden and Kishida focused their attention on a series of Asian diplomatic gatherings to improve ties. Chinese President Xi Jinping’s attendance at the G20 Meeting in Bali and APEC gathering in Bangkok proffered the opportunity finally for in-person bilateral meetings for both leaders. Finally, Japan’s long awaited strategic documents were unveiled in December. A new National Security Strategy (NSS) took a far more sober look at China’s growing influence and included ongoing concerns over North Korea as well as a growing awareness of Japan’s increasingly difficult relationship with Russia.

Accompanying the NSS is a 10-year defense plan, with a five-year build-up commitment, that gave evidence that Kishida and his ruling coalition were serious about their aim to spend 2% of Japan’s GDP on its security. The desire for greater lethality was also there, with the inclusion of conventional strike investment.

US - Japan

May — August 2022Abe’s Legacy and the Alliance Agenda

It was a busy summer for the United States and Japan. President Joe Biden visited Asia, stopping first in Seoul to meet new South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol, and then spending two days in Tokyo for a bilateral summit with Prime Minister Kishida Fumio and a follow-on meeting with the two other leaders of the Quad, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Australia’s newly elected prime minister, Anthony Albanese. Biden announced his Indo-Pacific Economic Framework in Tokyo with Kishida by his side. Economic security legislation in both Japan and the United States revealed the unfolding strategic calculations for the alliance. National efforts to enhance economic productivity and resilience included efforts to ensure reliable supply chains for Japanese and US manufacturers as well as the desire for greater cooperation among the advanced industrial economies to dominate the next generation of technological innovation. State investment in attracting semiconductor suppliers to Japan and the United States demonstrate the urgency with which both governments seek to diminish reliance on critical technology imports.

Despite all the diplomatic planning that accompanied these developments, the summer was not without surprises. In Japan, the sudden death of former Prime Minister Abe Shinzo, at the hand of a lone gunman, shocked a nation known for its relatively low rate of gun violence. Across the globe, leaders praised Abe’s statesmanship and his strategic vision—his ability to meet Japan’s moment of challenge as the rules-based order was under threat.

Only weeks later, the United States and China found themselves in a high-stakes military standoff over Taiwan. US Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi rescheduled her Asia tour after having to cancel it in April due to COVID-19. Her itinerary leaked, and her intention to visit Taiwan drew China’s ire. A top commentator for the Global Times tweeted that China’s People Liberation Army (PLA) had the right to shoot down Pelosi’s plane if she did. And a highly charged demonstration of Chinese military power ensued. The PLA exercises conducted after her departure directly involved Japan as missiles landed in its exclusive economic zone (EEZ). The United States ensured that its military was close at hand to dissuade miscalculation.

US - Japan

January — April 2022Russian Invasion Accelerates Alliance Review

The US and Japan began the year with a 2+2 meeting, continuing their close coordination on alliance preparedness and regional coalition-building. COVID-19 affected the two allies’ diplomatic schedule, however, as the omicron variant spread quickly in Washington, DC. Once again, an in-person meeting between the secretaries of state and defense and their counterparts, ministers of foreign affairs and defense, had to be moved online. Moreover, resolving the management of COVID by US Forces Japan with Japan’s own protocols was on the agenda. But the US and Japanese governments met another challenge with alacrity: the conclusion of a new Host Nation Support agreement. With an emphasis on alliance resilience, this five-year provision of Japanese support for the US military in Japan handily sidestepped some of the political difficulties that have colored talks in the past.

Much is ahead for Japan this year in updating its strategic planning. Prime Minister Kishida Fumio began a strategic review late last year, and the National Security Council as well as the Ministry of Defense got to work on laying out the aims of a new National Security Strategy, 10-year defense plan, and an accompanying procurement plan. Shaped by the accelerating shift in the military balance in Japan’s vicinity and across the Indo-Pacific, this strategic review is expected to be momentous. The Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) also initiated its own study of Japan’s strategic needs and produced a draft that highlights doubling Japan’s defense spending to match NATO’s target of 2% of GDP.

But President Biden and Prime Minister Kishida have focused on Europe since Russia invaded Ukraine. Both allies have been in sync as the G7 mobilized to impose sanctions against Russia and aid to Ukraine. Framing this crisis as a violation of the postwar international order, Kishida firmly committed Japan to ongoing and comprehensive engagement with not only the US but also European nations. Moreover, Putin’s war against Ukraine has galvanized dialogue between US allies in NATO and in Asia, creating a deepening diplomatic opportunity for Japan to develop European support should a similar crisis erupt in the Indo-Pacific.

US - Japan

September — December 2021A New Prime Minister and a Growing Alliance Agenda

2021 demonstrated the difficult politics that have attended the COVID-19 pandemic. In the United States, the Congressional certification of the presidential election became the focus of violent protest and an attempted insurrection to stop the transfer of power from Donald Trump to Joseph Biden. In Japan, while less volatile, the post-Abe era revealed the fragile balance of power within the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) that threatened to unseat unpopular prime ministers. The year began with Prime Minister Suga Yoshihide but ended with Prime Minister Kishida Fumio as Suga’s public approval ratings plummeted in response to the government’s pandemic management and the troublesome Tokyo Olympics. Japan’s two elections, one for the leadership of the LDP and the other for the Lower House, revealed just how sticky conservative politics are today. Undoubtedly, the election within the party drew the most interest as four new candidates emerged to claim the mantle of leadership of Japan’s largest political party.

Kishida emerged victorious after a second round of voting, which privileged those in the Diet over the rank and file of the party, with a far more assertive stance on Japan’s strategic outlook. He then led his party to victory in the general election, overcoming an opposition coalition that continued to struggle to put forward a cohesive identity or policy agenda.

Diplomatically, Washington and Tokyo continued to focus on their Indo-Pacific cooperation. The two militaries have continued consultations on how to cope with China’s growing presence in and around Japan’s southwestern islands. A new prime minister offered opportunity to further define the scope of US-Japan cooperation, and a new Biden-Kishida agenda is in the works. COVID-19 again intervened to prevent in-person meetings, but a virtual US-Japan 2+2 meeting allowed for continued alliance problem-solving.

US - Japan

May — August 2021Summer Takes an Unexpected Turn

By the end of spring, the US-Japan relationship was centerstage in the Biden administration’s Indo-Pacific diplomacy. From the first Quad (virtual) Summit to the visit of Prime Minister Suga Yoshihide to Washington, DC, relations between Tokyo and Washington could not have been better. A full calendar of follow-up meetings for the fall suggested even further deepening of the partnership. And on Aug. 20, President Joe Biden announced that he intended to nominate Rahm Emanuel, former mayor of Chicago and chief of staff for President Obama, as ambassador to Japan. Throughout the summer, the US and Japan continued to deepen and expand the global coalition for Indo-Pacific cooperation. The UK, France, and even Germany crafted their own Indo-Pacific visions, as did the EU. Maritime cooperation grew as more navies joined in regional exercises. Taiwan featured prominently in US-Japan diplomacy, and in May the G7 echoed US-Japan concerns about rising tensions across the Taiwan Straits. Japanese political leaders also spoke out on the need for Japan to be ready to support the US in case tensions rose to the level of military conflict.

US - Japan

January — April 2021Suga and Biden Off to a Good Start

The early months of 2021 offered a full diplomatic agenda for US-Japan relations as a new US administration took office. Joe Biden was sworn in as the 46th president of the United States amid considerable contention. Former President Donald Trump refused to concede defeat, and on Jan. 6, a crowd of his supporters stormed the US Capitol where Congressional representatives were certifying the results of the presidential election. The breach of the US Capitol shocked the nation and the world. Yet after his inauguration on Jan. 20, Biden and his foreign policy team soon got to work on implementing policies that emphasized on US allies and sought to restore US engagement in multilateral coalitions around the globe. The day after the inauguration, National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan reached out to his counterpart in Japan, National Security Secretariat Secretary General Kitamura Shigeru, to assure him of the importance the new administration placed on its allies. The COVID-19 pandemic continued to focus the attention of leaders in the United States and Japan, however.

US - Japan

September — December 2020Leadership Transitions in Tokyo and Washington

2020 brought a global pandemic, economic strain, and, in both the United States and Japan, leadership transitions. COVID-19 came in waves, smaller to be sure in Japan than in the United States, and each wave intensified public scrutiny of government. Neither Tokyo nor Washington held up well. Public opinion continued to swing against President Donald Trump, increasing his disapproval rating from 50% in January to 57% in December following the US presidential election. Prime Minister Abe Shinzo also suffered a loss of confidence. His disapproval rating grew from 40% in January to 50% in July, cementing his decision to step down on Aug. 28, ostensibly for health reasons.

US - Japan

May — August 2020Unexpected Turbulence for the Alliance

Several unexpected events during the summer of 2020 confounded US-Japan ties. The COVID-19 pandemic continued to challenge governments in Tokyo and Washington, as the number of infected grew. The scale of the pandemic’s impact was far greater in the United States, with new cases climbing in southern and western states. Japan’s metropolitan centers faced an uptick in cases, but so too did less populated regions. The mortality rate of the United States hovered at 3%, a far more worrisome indicator that the pandemic was far from contained. In contrast, Japan continued to have a relatively low mortality rate of 1.9%.

US - Japan

January — April 2020COVID-19 Overtakes Japan and the United States

It took time for Tokyo and Washington to understand the scope of the COVID-19 crisis, as the virus continues to spread in both Japan and the United States. The routine that would normally define US-Japan relations has been set aside, but it is too early to draw inferences about what this pandemic might mean for the relationship, for Asia, or indeed for the world. At the very least, the disease confounded plans in the United States and Japan for 2020. COVID-19 upended the carefully developed agenda for post-Abe leadership transitions in Japan and threw President Trump, already campaigning for re-election in the November presidential race, into a chaotic scramble to cope with the worst crisis in a century.

US - Japan

September — December 2019The Finale for Abe-Trump Alliance Management?

The highlight of 2019 was undoubtedly the US-Japan trade deal. It was two years in the making, but in September, Japanese Prime Minister Abe Shinzo and US President Donald Trump concluded their much-anticipated trade agreement, ending a worrisome source of dissonance in the relationship. Two focal points characterized this first step in resolving trade frictions: market access in Japan for US agricultural goods and a new set of rules for digital trade. However, Abe got some pushback at home, and the Trump administration cautioned that this was just the first step to redressing the deficit.

US - Japan

May — August 2019A Busy Summer of Bilateralism

Relations between the United States and Japan were active over the summer with two visits by President Donald Trump to Japan. The first was for Trump and First Lady Melania Trump to be the first state guests of the new Reiwa Era. The second was to participate in the G20 Summit in Osaka. Meanwhile, the two countries engaged in a series of trade talks that produced the broad outline of an agreement that is expected to be signed in late September. Throughout, domestic politics played an important role with upper house elections in Japan and Trump’s threat of tariffs influencing the pace of trade negotiations. In coming months, the US presidential election campaign will likely continue to shape alliance management.

US - Japan

January — April 2019Treading Water in Choppier Surf

The US and Japanese governments continued to work at maintaining a steadfast alliance, yet there were issues that could upend the relationship. After several months of anticipation, there was some progress on trade negotiations. While the US hoped to close the deal before President Trump visits Japan in late May, differences over the scope of the agreement and a number of difficult issues related to automobiles, agriculture, and currency rates remained. Meanwhile, domestic pressure over the Futenma relocation project returned to the news with a new referendum that strongly rejected the move. The introduction of the Reiwa era at the end of April served as a brief respite as the alliance partners sought to align interests following the “no deal” US-DPRK summit in Hanoi.

US - Japan

September — December 2018Stability in Tokyo, Disruption in Washington

2018 came to a relatively quiet close for the US and Japan. Prime Minister Abe Shinzo secured a third term as leader of the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) in a party election on Sept. 20 and is now set to be Japan’s longest serving prime minister. In contrast, President Donald Trump faced an electoral setback in the November midterms. With Democrats taking over the House of Representatives in January, pressure on the administration will grow. In December, Trump dismissed Chief of Staff John Kelly and Defense Secretary James Mattis, and locked horns with the incoming Democratic Party leadership over funding for his border wall. Nevertheless, the US-Japan relationship seemed steady. In September, Prime Minister Abe agreed to open bilateral trade talks and in return sidestepped the Trump administration’s looming auto tariffs. Yet there are differences over their goals, suggesting that continued compromise will be needed. Abe worked hard in numerous summits to position Japan in Asia in the final months of 2018. He visited China, hosted India’s prime minister in Tokyo, and restarted the negotiations with Russia on the northern territories. Japan also announced its next long term defense plan and a five-year, $240 billion implementing procurement plan that includes a considerable investment in modern US weapon systems.

US - Japan

May — August 2018Summer Before the Storm?

Relations between Tokyo and Washington grew more complex over the summer. The decision by President Donald Trump to meet North Korean leader Kim Jong Un marked a new phase of alliance coordination on the strategic challenge posed by Pyongyang. Trade relations also continued to create an undercurrent of discord. No consensus emerged on a free-trade agreement and the sense that the Trump administration was preparing to impose tariffs not only on steel and aluminum but also on the auto industry added to trepidation over the economic relationship. By the end of the summer, there were signs that the US and Japan were beginning to synchronize their approaches to the Indo-Pacific region as an economic cooperation agenda seems to be emerging. Meanwhile, politics in both capitols this fall make predictions about policy coordination difficult. Prime Minister Abe Shinzo faces his party’s leadership election on Sept. 20, a contest he is likely to win but an opportunity for others in the party to push him on his priorities. In the US, midterm elections promise a referendum on the Trump administration and the increasing turmoil surrounding the White House.

US - Japan

January — April 2018Adjusting to Abrupt Diplomacy

2018 brought with it a swirling series of summits, including another visit by Prime Minister Abe Shinzo to the United States to meet President Donald Trump. The year began with Japan and the United States toe-to-toe on their “maximum pressure” strategy toward North Korea. Four months later there was the announcement of a June 12 summit between Trump and North Korea’s leader Kim Jong Un. Tokyo and Washington have yet to come together on trade, and even at the Abe-Trump summit in mid-April, the differences were conspicuously on display. The US-Japan economic partnership remains a potential black hole for the alliance in the months ahead. But the action is in Northeast Asia for the moment, where everyone seems to be trying to meet with everyone. Nonetheless, Abe and Trump made clear in their summit their mutual goal has not changed: complete, verifiable, and irreversible denuclearization by North Korea.

US - Japan

September — December 2017Trump Visits Tokyo Amid North Korea Tensions

In the fall of 2017, the growing threat from North Korea garnered a lot of attention in the US and Japan. In Japan, Prime Minister Abe Shinzō used that threat to win yet one more election. North Korea also dominated discussions during President Donald Trump’s visit in November, although a reckoning on trade hovered in the background. Japan also worried about other stops on Trump’s extended Asian itinerary, especially his stay in Beijing. The Trump administration’s focus on its America First agenda was a significant factor in shaping Japan’s foreign policy. Abe seemed up to the challenge as Japan actively pursued its interests globally to ensure support for North Korea sanctions and to build trade agreements that will further Japan’s economic and trade interests. The US-Japan alliance remains in good shape, although there are difficulties to manage.

US - Japan

May — August 2017A Summer of Setbacks

The summer of 2017 was an uneasy one in both Tokyo and Washington. In Japan, Prime Minister Abe Shinzo struggled as public approval dropped precipitously following scandals and a miserable performance for his party in the Tokyo metropolitan elections. In the US, President Donald Trump moved from conflict to conflict, resulting in a historically low approval rating for a new administration and deep fissures within the Republican Party. Alliance cooperation largely focused on the continuing tensions with North Korea. A long-awaited Japan-US Security Consultative Committee (2+2 Meeting) between the defense and foreign policy principals could not be scheduled until after Abe reshuffled his Cabinet in August. While the discussions proved cordial, there was little indication that a strategic look ahead was in the making. Troubles at home for both administrations seemed to forestall any effort at a comprehensive US-Japan discussion about the Asia-Pacific region.

US - Japan

January — May 2017Tokyo Transitions to Trump

The transition to the new Trump administration was far smoother for Japan than for other US allies. Prime Minister Abe Shinzo’s visit to Trump Tower the week after the election in November undoubtedly helped smooth the way, and his visit in February proved to be a successful confirmation of Tokyo’s highest priorities for alliance cooperation. Secretary of Defense James Mattis and Secretary of State Rex Tillerson both headed to Northeast Asia, reassuring Tokyo and Seoul of the administration’s commitment to its Asian allies. This early effort helped ensure continuity rather than disruption would be the theme for the US-Japan alliance for the next four years. North Korea, of course, helped that return to normalcy. Yet not all was settled in these early months. How the new administration was going to define its approach to trade remained ill-defined. The Japanese government, however, was not interested in a conversation that focused only on trade.

US - Japan

September — December 2016US-Japan Relations and the Trump Effect

The US presidential election was the primary influence affecting US-Japan relations in the fall of 2016. Japan was brought into the spotlight during the campaign with Trump repeatedly criticizing Tokyo for unfair trade practices and free riding in the alliance. The outcome of the election left many Japanese worried about the future of the alliance. Prime Minister Abe quickly reached out to President-elect Trump, arranging a meeting with him in New York on Nov. 18. Beyond the attention given to the election, the LDP and Abe also sought to support the Obama administration by ratifying the Trans-Pacific Partnership and promoting maritime capacity building in Southeast Asia. President Obama and Prime Minister Abe met for the last time in Hawaii on Dec. 27. Uncertainty abounds on the economic and strategic fronts in the coming year, but the biggest unknown for the bilateral relationship will be the new US president and his approach to Asia.

US - Japan

May — August 2016Hiroshima to The Hague

President Obama and Prime Minister Abe traveled to Hiroshima, where Obama took the opportunity to speak of the devastating consequences of war in the nuclear era. The summer months that followed were full of politics, with an Upper House election in Japan in July and the Republican and Democratic Party conventions in the US kicking off the general election campaign for president. The Obama administration continued to work toward congressional passage of the Trans-Pacific Partnership at the end of the year. With less political contention but growing skepticism over Washington’s ability to ratify the agreement, the Abe Cabinet decided to postpone Diet discussions on the topic until after its election. Regional relations continue to shape the US-Japan alliance agenda with Chinese maritime activity in the East China Sea and South China Sea and ongoing North Korean provocations garnering the most attention.

US - Japan

January — April 20162016 Opens with a Bang

The US-Japan relationship was relatively steady in the early months of 2016 until the US presidential primaries began to stir things up. For the first time in decades, Japan became the focus of debate on the campaign trail when Donald Trump began to single out Japan on trade and on security cooperation. There was also a setback on the Futenma replacement facility when construction was halted following a compromise between the central government and Okinawa that calls for a court decision on how to proceed. Nevertheless, the two governments continued to refine alliance coordination in the face of North Korea’s nuclear test and missile launches and pursued maritime cooperation as Beijing’s behavior in the South China Sea continued to roil regional waters. With major elections on the horizon, both countries are likely to be consumed by politics in the coming months.

US - Japan

September — December 2015Official Cooperation, Domestic Challenges

Washington and Tokyo made significant progress on two new initiatives this fall – Japan’s implementation of legislation for the exercise of collective self-defense and the conclusion of negotiations with other participants in the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP). With Japanese Upper House elections in the summer and US presidential elections in the fall, trade, military strategy, and US-Japan security cooperation will be part of the political discourse in both countries. Along with the ratification process for the Trans-Pacific Partnership trade deal, two challenges for Washington and Tokyo that will continue into the new year are how to respond to Chinese land reclamation in the South China Sea and how to deal with local opposition to Tokyo’s plans for building a new airfield to replace the Futenma facility on Okinawa.

US - Japan

May — August 2015History and Other Alliance Constraints

In the wake of a highly successful April visit by Prime Minister Abe Shinzo to Washington, the US-Japan relationship seemed poised for a celebration of success in revamping the alliance. Two focal points of alliance policymakers were the Guidelines for US-Japan Defense Cooperation and the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP). But over the summer, both of these initiatives came under political scrutiny. Beyond alliance priorities, the US and Japan faced additional dilemmas in how to deal with a more assertive and sensitive China. Artificial island building by China in the South China Sea brought the US and Japan into closer dialogue over regional maritime cooperation. At the end of the summer, the much-anticipated commemorations of the end of World War II in Japan and China brought heightened sensitivity to the region.

US - Japan

January — April 2015Strategic Alignment

Benefiting from a window of political stability, the Abe government continued to focus on the twin pillars of economic strategy and defense policy reform. Bilateral engagement on security, trade, and regional and global issues informed the agenda for the prime minister’s official visit to Washington in late April, the first by a Japanese leader in nine years. Abe also became the first Japanese leader to address a joint session of Congress and relayed the main themes from his summit with President Obama by reflecting on the 70th anniversary of the end of World War II, celebrating the evolution of the US-Japan alliance, and outlining a strategic vision for the future.

US - Japan

September — December 2014Heading to the End Zone on TPP and Defense

Weak economic data prompted Prime Minister Abe Shinzo to postpone painful tax increases and call a snap election to extend the window in which to advance his policy agenda. US-Japan negotiations on TPP slowed, but President Obama made his first significant public push in December on TPP. Discussions on revising the bilateral defense guidelines advanced somewhat but were extended into 2015 to better coincide with the legislative debate in Japan on defense policy. Trilateral coordination with Australia and South Korea reflected a shared commitment to network the alliance agenda. Public opinion surveys revealed a foundation of support for the US-Japan relationship across a range of issue areas. All of the bilateral agenda on defense and trade was aimed at a potential Abe visit to Washington in the spring.

US - Japan

May — August 2014Pursuing a Path Forward

The Abe government outlined an economic growth strategy and introduced a package of defense policy reforms aimed at enhancing Japan’s leadership role on security. Bilateral dialogue on security cooperation and military exercises featured prominently, complemented by trilateral coordination with other US allies on the margins of multilateral gatherings in the region. The two governments conducted several rounds of bilateral trade negotiations related to the Trans-Pacific Partnership but were unable to make progress on sensitive market access issues that threatened to prolong efforts to boost the economic pillar of the alliance.

US - Japan

January — April 2014The Sushi Summit

The Abe government focused on the economy, energy strategy, and defense policy reform but the timeline for implementing these pillars of Abe’s agenda was uncertain. A flurry of bilateral diplomacy paved the way for various initiatives including a trilateral summit with South Korean President Park Geun-hye and President Obama in The Hague. Obama made a state visit to Japan highlighting areas for strategic cooperation between Japan and the United States but the two governments were not able to conclude a bilateral trade agreement that would strengthen the economic pillar of the alliance.

US - Japan

September — December 2013Big Steps, Big Surprises

Prime Minister Abe continued to focus on the economy but also introduced diplomatic and defense strategies as his first year in office came to a close. The US and Japanese governments participated in TPP trade negotiations and bilateral talks but could not resolve differences on agricultural liberalization and market access for automobiles. A meeting of the bilateral Security Consultative Committee set forth priorities for defense cooperation, and China’s announcement of its East China Sea ADIZ put bilateral coordination to the test. The governor of Okinawa approved a landfill permit for the Futenma Replacement Facility on Okinawa, establishing some momentum for the realignment of US forces there. Prime Minister Abe’s visit to Yasukuni Shrine disappointed the Obama administration and sparked major debate in the US, but was not expected to upend bilateral diplomacy.

US - Japan

May — August 2013Abe Settles In

Prime Minister Abe focused intently on economic policy and led his Liberal Democratic Party to a resounding victory in the July Upper House election, securing full control of the Diet and a period of political stability that bodes well for his policy agenda. Multilateral gatherings in Asia yielded several opportunities for bilateral and trilateral consultations on security issues, and the economic pillar of the alliance also took shape with Japan’s entry into the Trans-Pacific Partnership negotiations and discussions on energy cooperation. Comments on sensitive history issues sparked controversy but did not derail bilateral diplomacy. The nomination of Caroline Kennedy as US ambassador to Japan marks a new chapter in the relationship.

US - Japan

January — April 2013Back on Track

Prime Minister Abe Shinzo generated a buzz in the media and the markets by introducing a three-pronged economic strategy designed to change expectations for growth as his ruling Liberal Democratic Party prepares for a parliamentary election in July. President Obama hosted Abe in Washington for a summit that paved the way for Japan’s inclusion in the Trans-Pacific Partnership trade negotiations. Bilateral coordination on regional security and defense cooperation accelerated with high-level visits in both capitals to reaffirm the vitality of the alliance. The reemergence this spring of tensions between Japan and its neighbors over history issues was the only wrinkle in an extremely productive period in US-Japan relations.

US - Japan

September — December 2012Meet the New Boss/Same as the Old Boss?

The Liberal Democratic Party won a Lower House election in a landslide and Abe Shinzo became prime minister for the second time amid public frustration with poor governance and anemic economic growth. The United States and Japan continued a pattern of regular consultations across a range of bilateral and regional issues with tensions between Japan and China over the Senkaku Islands and another North Korean missile launch topping the diplomatic agenda. The US military presence on Okinawa also featured with the deployment of the V-22 Osprey aircraft to Okinawa and the arrest of two US servicemen in the alleged rape of a Japanese woman. The year came to a close with Prime Minister Abe hoping for a visit to Washington early in 2013 to establish a rapport with President Obama and follow through on his election pledge to revitalize the US-Japan alliance.

US - Japan

May — August 2012Noda Marches On; Both Sides Distracted?

Prime Minister Noda advanced a legislative package on tax and social security reform but faced stiff political headwinds in the form of a frustrated public and a jaded opposition steeling for an election. Japanese concerns over the safety of the MV-22 Osprey aircraft scheduled for deployment in Okinawa dominated the bilateral agenda – at least in the media – and tested the mettle of Japan’s widely-respected new defense minister. The two governments agreed to continue consultations on Japan’s interest in the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) but political paralysis in Japan and presidential politics in the United States could complicate efforts to make progress in the near term. Two reports issued over the summer addressing US force posture strategy in the Asia-Pacific and the agenda for US-Japan alliance, respectively, focused on the future trajectory for the bilateral relationship.

US - Japan

January — April 2012Back to Normal?

After three tumultuous and frustrating years as the DPJ tried to find its legs, Prime Minister Noda finally visited Washington. Noda has been busy pursuing an increase in the consumption tax, trying to gain support for some continuation of nuclear power, cobbling together domestic support for Japanese participation in the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) negotiations, and facing the perennial struggle on relocating Marine Corps Air Station Futenma on Okinawa. By the time of his visit, Noda had started to line up support for the consumption tax, backed off temporarily on TPP, and waited on restarting nuclear plants. However, he did manage to complete an agreement to de-link the move of about 9,000 US Marines to Guam and other locations in the Pacific from the Futenma relocation issue. That announcement was a rare victory and set a positive tone for the summit and the joint statement pledged to revitalize the alliance. The prime minister returned home to face the same domestic political challenges, but with an important if limited accomplishment in foreign policy.

US - Japan

September — December 2011Big Points on the Scoreboard But Can Noda Make It?

Prime Minister Noda accomplished important steps including the selection of the F-35 as Japan’s next-generation fighter, relaxing the three arms export principles, and announcing a decision to join negotiations for the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) – all of which demonstrated the current Japanese government’s readiness to revive the economy and strengthen security ties and capabilities. At the same time, the government’s support rate began to collapse in a pattern eerily similar to Noda’s five predecessors, raising questions about the ability of the government to follow through on the more challenging political commitments related to TPP. President Obama met Noda at the United Nations in New York and at the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) forum in Hawaii in an active season of bilateral diplomacy. Public opinion surveys revealed generally positive views of the US-Japan relationship in both countries but the impasse over relocating Marine Corps Air Station Futenma fueled negative perceptions in Japan.

US - Japan

May — August 2011Kicking the Kan down the Road

Kan Naoto resigned as prime minister on Aug. 26 after promising to step aside almost three months earlier amid dissension within his ruling Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ) and dwindling public support after a clumsy response to the tragedies of March 11. He was succeeded by Finance Minister Noda Yoshihiko, who prevailed in the DPJ presidential race despite little evidence of support in the polls, but strong backing within the party. The US and Japan convened the first Security Consultative Committee or “2+2” in four years to outline common strategic objectives and strengthen alliance cooperation in a regional and global setting. The two governments also consulted on the margins of international events to discuss cooperation on various issues. Vice President Joseph Biden visited Japan in late August to reiterate US support for the recovery effort and met victims of the disaster in Tohoku. Public opinion polls in Japan and the United States revealed a solid foundation of support for the US-Japan alliance.

US - Japan

January — April 2011Responding to Multiple Crises

The earthquake, tsunami, and nuclear disaster that struck Japan on March 11 tested the leadership credentials of the Kan government and the capacity for alliance coordination in response to simultaneous crises. With the exception of disconnects in assessing the nature of the nuclear emergency at the Fukushima Daiichi plant, the March 11 tragedy revealed the strength of the alliance as the Obama administration further demonstrated US solidarity with Japan by announcing a partnership for reconstruction to support Japan’s recovery. Prime Minister Kan reshuffled his Cabinet for the second time and unveiled a policy agenda aimed at “the opening of Japan” but faced scrutiny for failing to usher budget-related legislation through a divided Diet. Bilateral diplomacy proceeded apace and was aimed at advancing economic and security cooperation though a controversy over alleged remarks about Okinawa by a senior US diplomat had the potential to cause another crisis in the alliance.

US - Japan

October — December 2010Tempering Expectations

Prime Minister Kan Naoto opened the quarter with a speech promising a government that would deliver on domestic and foreign policy, but public opinion polls indicated he was failing on both fronts, damaging his own approval rating and that of the ruling Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ). The US and Japanese governments continued a pattern of coordination at senior levels and North Korea’s bombardment of Yeonpyeong Island on Nov. 23 furthered trilateral diplomacy with South Korea and exchanges among the three militaries. President Obama met with Kan on the margins of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) Leader’s Meeting in Yokohama to take stock of the relationship, though a once-anticipated joint declaration on the alliance did not materialize and the optics of the meeting appeared designed to lower expectations as the Futenma relocation issue remained unresolved. A bilateral public opinion survey on US-Japan relations released at the end of the quarter captured the current dynamic accurately with Futenma contributing to less sanguine views but convergence in threat perception and an appreciation for the role of the alliance in maintaining regional security as encouraging signs for the future.

US - Japan

July — September 2010Hitting the Reset Button

The ruling Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ) suffered an embarrassing defeat in the July Upper House election less than a year after assuming power. Prime Minister Kan Naoto subsequently took a beating in the polls but managed to withstand a challenge from former DPJ Secretary General Ozawa Ichiro in a party presidential election marked by heated debate over economic policy. Political turmoil did not preclude active diplomacy on the part of Kan’s government, nor coordination between Washington and Tokyo on a range of bilateral, regional, and global issues including the relocation of Marine Corps Air Station (MCAS) Futenma on Okinawa; a collision between a Chinese fishing boat and Japanese Coast Guard vessels near the Senkaku Islands; and sanctions on Iran to condemn its nuclear activities. The quarter came to a close with President Obama and Prime Minister Kan taking stock of a rapidly developing bilateral agenda during a brief yet productive meeting on the margins of the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) in New York, setting the stage for the president’s trip to Japan in November.

US - Japan

April — June 2010New Realism

The relocation of Marine Corps Air Station Futenma on Okinawa remained the predominant issue in the US-Japan relationship and the two governments issued a joint statement in late May reaffirming a commitment to realize a plan adopted in 2006 with some modifications to be explored. Prime Minister Hatoyama then resigned as polls revealed frustration with his handling of the Futenma issue and weak leadership overall. Finance Minister Kan Naoto succeeded Hatoyama as premier and outlined his own policy priorities just weeks before an important parliamentary election. Kan stressed the centrality of the US-Japan alliance to Japanese diplomacy and reiterated the theme in his first meeting with President Obama at the G8 Summit in late June. The two leaders’ first meeting was business-like and lacking for drama – exactly as both governments had hoped. New public opinion polls suggested political turmoil at home has not had a significant impact on Japan’s standing globally or in the US, but some observers continued to suggest the US should lower expectations of Japan as an ally in the debate about the future of the alliance.

US - Japan

January — March 2010Many Issues, a Few Bright Spots

Prime Minister Hatoyama Yukio moved to implement his domestic policy agenda with an eye toward the Upper House elections this summer but watched his approval rating fall as he and members of his ruling Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ) were beset by political fundraising scandals. The impasse over the relocation of Marine Air Station Futenma continued to dominate the bilateral agenda and alternative proposals put forth by the Hatoyama government failed to advance the discussion. Concerns about barriers to US exports and the restructuring of Japan Post emerged in commentary by the Obama administration and congressional leaders but a joint statement highlighting cooperation on the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation forum (APEC) reinforced the economic pillar of the relationship. The Toyota hearings in Congress were covered extensively by media in both countries but did not have an immediate impact on US-Japan relations. However, the recall issue and other developments point to potentially negative perceptions that could cloud official efforts to build a comprehensive framework for the alliance over the course of the year, the 50th anniversary of the 1960 US-Japan Security Treaty.

US - Japan

October — December 2009Adjusting to Untested Political Terrain

In the last quarter of 2009, the US-Japan alliance entered one of the greatest periods of uncertainty in recent memory. Many of the populist policy proposals of the Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ) fell by the wayside as the party settled into power after trouncing the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) in August elections. Fiscal and political realities forced Prime Minister Hatoyama Yukio to shelve several key domestic pledges. On the foreign policy front, the new government announced Japan would terminate a naval refueling mission supporting coalition operations in Afghanistan, as it had pledged during the campaign, but unveiled a $5 billion aid package focused on infrastructure and vocational training. President Obama and Prime Minister Hatoyama met in Tokyo in November to discuss Afghanistan and several other issues including North Korea, nonproliferation, and climate change. However, the summitry did little to conceal Washington’s frustration with Tokyo’s conflicting messages about the US-Japan alliance. Obama came away from the summit believing that Hatoyama had promised to implement the current bilateral agreement on realigning bases in Okinawa; instead, Hatoyama announced that he would make a decision on how to proceed in the late spring after exploring other options that the Obama administration and Hatoyama’s own ministers of foreign affairs and defense had already dismissed as unrealistic. The Obama administration was also chagrined to see Hatoyama pledge to other Asian leaders that Japan would move forward with an ill-defined “East Asia Community” in order to reduce Tokyo’s “dependence” on the United States. Public opinion polls in Japan revealed dissatisfaction with Hatoyama’s approach to the Okinawa issue and his leadership skills overall, while opinions toward the US hit their highest mark ever. Nevertheless, the difficulties managing the alliance cast a shadow over bilateral discussions on how to mark the 50th anniversary of the bilateral security treaty in 2010.

US - Japan

July — September 2009Interpreting Change

Hatoyama Yukio led the Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ) to a landslide victory in the Aug. 30 Lower House election and was elected prime minister after a spirited campaign for change both in the form and substance of policymaking. Exit polls showed that the public had grown weary of the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) but had not necessarily embraced the agenda of the coalition government Hatoyama would subsequently form with an eye toward consolidating power in an Upper House election next summer. Though the election centered primarily on domestic policy, Hatoyama began his tenure by outlining foreign policy priorities during visits to the UN in New York and the G20 summit in Pittsburgh less than a week after he took office.

The Obama administration emphasized respect and patience as Japan experienced a transition to a non-LDP government for only the second time since 1955. Senior U.S. officials visited Tokyo for consultations soon after the election and prepared for the first meeting between President Obama and Prime Minister Hatoyama in New York on Sept. 23. The leaders reaffirmed the importance of the U.S.-Japan alliance and set the stage for a visit to Japan by Obama in November. The quarter ended with good atmospherics but also questions about the extent to which Hatoyama would try to implement several campaign pledges – such as renegotiating the realignment plan for U.S. forces on Okinawa – with the potential to strain bilateral ties.

US - Japan

April — June 2009Coordination amid Uncertainty

Most analysts had thought this quarter would begin with the dissolution of the Lower House of the Diet and elections, but Prime Minister Aso Taro put off the election with the hope that additional economic stimulus measures would translate into increased support for his ruling Liberal Democratic Party. The stimulus package helped a bit, but Aso received a real boost when Ozawa Ichiro resigned as opposition leader in May due to a funding scandal. That boost in the polls quickly evaporated when Ozawa was succeeded as head of the Democratic Party of Japan by Hatoyama Yukio. Revelations that an aide had falsified his political funding reports for several years tarnished Hatoyama’s image, but did not help Aso and the government raise their support rate beyond the low teens in many polls. As a result, most analysts continued to predict a victory for the DPJ in a general election expected in August and uncertainty continued hanging over the U.S.-Japan relationship because neither political party in Japan is likely to win a landslide – meaning another year or more of parliamentary gridlock.

Japan’s political mess did not get in the way of close U.S.-Japan coordination in response to a series of North Korean provocations, including missile tests and the detonation of a nuclear device. President Obama also made progress in nominating key personnel to guide the U.S.-Japan relationship including the nomination of attorney John Roos for ambassador to Japan and the confirmation of Kurt Campbell as assistant secretary of state for East Asia and Pacific affairs. The quarter came to a close with the U.S. Congress gearing up for a budgetary battle with the Obama administration over the future of the F-22 stealth fighter, which the Aso administration has said it wants to buy, and Secretary of Defense Gates has said he does not intend to sell.

US - Japan

January — March 2009A Fresh Start

A new calendar year did little to change the tenor of Japanese domestic politics as the public became increasingly frustrated with parliamentary gridlock and the leadership of Prime Minister Aso Taro, whose approval rating plummeted amid a deepening recession. Opposition leader Ozawa Ichiro continued pressure tactics against the government and became the favorite to succeed Aso until the arrest of a close aide damaged his reputation and stunted momentum for a snap election. Aso demonstrated the art of political survival, touting the urgency of economic stimulus over a poll he could easily lose and which need not take place until the fall. In an effort to prevent political turmoil from weakening Japan’s global leadership role, the government dispatched two Maritime Self-Defense Force (MSDF) destroyers to participate in antipiracy operations in the Gulf of Aden.

The Obama administration wasted little time in establishing a positive trajectory for the U.S.-Japan alliance, first sending Secretary of State Hillary Clinton to Tokyo in mid-February and receiving Prime Minister Aso at the White House shortly thereafter. The core agenda items for both visits – the economic crisis, North Korea, Afghanistan, and climate change – reflected both regional and global challenges. Bilateral issues also featured prominently on the agenda in the form of an agreement on the relocation of U.S. forces from Okinawa to Guam. In a fitting end to a quarter of close bilateral coordination, Washington and Tokyo were poised to monitor an anticipated missile test by North Korea and orchestrate a cohesive response that could determine the fate of the Six-Party Talks.

US - Japan

October — December 2008Traversing a Rough Patch

The U.S. decision to rescind the designation of North Korea as a state sponsor of terrorism tested the bilateral relationship this quarter as the Bush administration was perceived in Japan as having softened its commitment to the abductee issue in favor of a breakthrough on denuclearization in the Six-Party Talks, which ultimately proved elusive. The Aso government managed to extend the Maritime Self-Defense Force (MSDF) refueling mission in the Indian Ocean for one year, though bilateral discussions on defense issues continued to center on whether Japan could move beyond a symbolic commitment to coalition operations in Afghanistan.

Japanese domestic politics remained tumultuous as the opposition led by the Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ) thwarted the Aso legislative agenda to increase pressure for a snap election. Prime Minister Aso’s approval rating plummeted over the course of the quarter due mostly to frustration with the response to the financial crisis, prompting him to postpone the widely anticipated Lower House election in an attempt to shore up support for the ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP). Public opinion polls revealed increased interest in offering the DPJ a chance at the helm with most observers predicting an election sometime next spring. Other polls at the end of the quarter showed the Japanese public less sanguine about the U.S.-Japan alliance, a sobering development as President-elect Obama prepared to take office.

US - Japan

July — September 2008Weathering Political and Economic Turmoil

The quarter began with President Bush and Prime Minister Fukuda meeting on the sidelines of the G8 summit in Hokkaido, but their bilateral agenda and Fukuda’s own premiership were eclipsed by dramatic political and economic developments in both countries. Fukuda resigned suddenly on Sept. 1 having failed to convince the public he could strengthen the economy and move important legislation through a divided legislature. Aso Taro won the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) presidential race in a landslide and began his tenure as prime minister stressing economic stimulus measures, the importance of the U.S.-Japan alliance, and Japan’s role as a global leader, but with uncertainty about whether his government would even survive to the end of the year. Ozawa Ichiro was re-elected president of the opposition Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ) and touted a populist manifesto to woo the public in anticipation of a Lower House election this fall. Meanwhile, the U.S. government struggled to contain a financial crisis that rattled world markets, prompting Japanese banks to take major stakes in ailing U.S. businesses. A successful ballistic missile defense test in September augured well for sustained bilateral defense cooperation, assuming defense budgets survive the current financial turmoil. And North Korea’s move toward reprocessing plutonium at Yongbyon threatened to erase the diplomatic progress made in the Six-Party Talks at a time when leaders in Washington and Tokyo already had plenty of diplomatic challenges and tough domestic elections to manage.

US - Japan

April — June 2008Looking toward Elections

The debate in the Japanese Diet remained contentious this quarter as opposition parties challenged the Fukuda government on several legislative issues including the gasoline tax, a new health insurance program for the elderly, and host nation support for U.S. forces. Fukuda’s approval rating fell suddenly due to public dissatisfaction with his domestic policy agenda but later rebounded enough to quell rumors of a Cabinet reshuffle prior to the Hokkaido G8 Summit in July. The arrest in early April of a U.S. serviceman charged with murdering a taxi driver in Yokosuka brought negative publicity for U.S. forces.